Archive

- January 2026

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- January 2023

- September 2022

- August 2022

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

Les Miserables

Many years ago I started reading Les Miserables, the novel with perhaps the greatest claim to be the Matter of France. I had grown up on the video recording of the 10th Anniversary Concert of the musical at Royal Albert Hall, which has always been far and away my favorite musical, so I was eager to finally dig into the book. I knew it was long; what I didn’t realize was that the entire first section was going to be an extremely detailed accounting of the everyday habits of an extremely charitable bishop. After seventy pages I paused, and didn’t pick up again until over a decade later (don’t worry, I started over from the beginning). This time I was surprised by just how easily all 1,222 pages went down—at no point did the novel drag, at no point did my interest flag, even when Hugo devotes an entire book to a description of the history and layout of the Parisian sewers so thorough that an engineer could probably use it to base a preliminary report on. Some of this is down to the excellent translation by Charles Wilbour, which I believe was the first translation into English, and which because of its contemporaneity with the novel carries with it the authenticity of the language of the day. The rest is down to Victor Hugo, who wrote what is probably going to go in my list as the third greatest novel I’ve read, after The Lord of the Rings and The Brothers Karamazov.

There is a whole world captured in all its complexity—not simply a perspective on the world, though Hugo voices his opinions with the confidence of a prophet, as he pulls together into one skein the whole complex tension of conflicting truths, and the full personhood, the imago Dei of every wretch on Earth. And it’s not simply a moment in time either—there are the judgements Hugo pronounces on history, whole worlds recalled in memory and nostalgia which had already ceased to exist when he set pen to paper, and then there is the world that shall be when tomorrow comes.

There were two aspects of the book which struck me most profoundly, one expected, one unexpected. The first is how much Hugo’s vivisection of the souls of Jean Valjean and Javert in their moments of crisis did not merely ring true, but actually mirror the precise patterns of guilty, anxious rumination that I remember from my own, much less dramatic, life. Several times Valjean goes through a dark night of the soul of exactly the sort I have lived my life fearing and trying to flee from. This is a story for people who, like Valjean, live in terror of what their conscience will demand of them, and for people like Javert, who are too afraid to ever accept unmerited grace. It is a book of truths which appear contradictory, but which are in fact inseparable.

The second aspect was how well Hugo’s magisterial pronouncements on history, humanity, progress, and the will of God put into words an apology for my own embryonic political theology. Hugo is both more clear-eyed about the darkest parts of humanity, and how deep those run, and more idealistic and hopeful than just about any other writer of fiction. In casting his gaze along the sweep of history’s rapid turning through the nineteenth century and into the future, he depicts what I can only call a non-Utopian eschatological progress. Hugo believes simultaneously in the importance of struggling to bring about a free world, to realize a millennial kingdom on earth that we each must help midwife, while also recognizing that our efforts will not bear fruit in our lives, that they will seem to fail completely, as the June rebellion did. The hope of fulfillment of this dream must rest firmly in God and eternity; and yet from God’s eternity, the inspiration breaking like the first fingers of dawn over the dim horizon should stir us to rise, even prematurely, and march East.

Quotes:

“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine, with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age—the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of woman by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.”

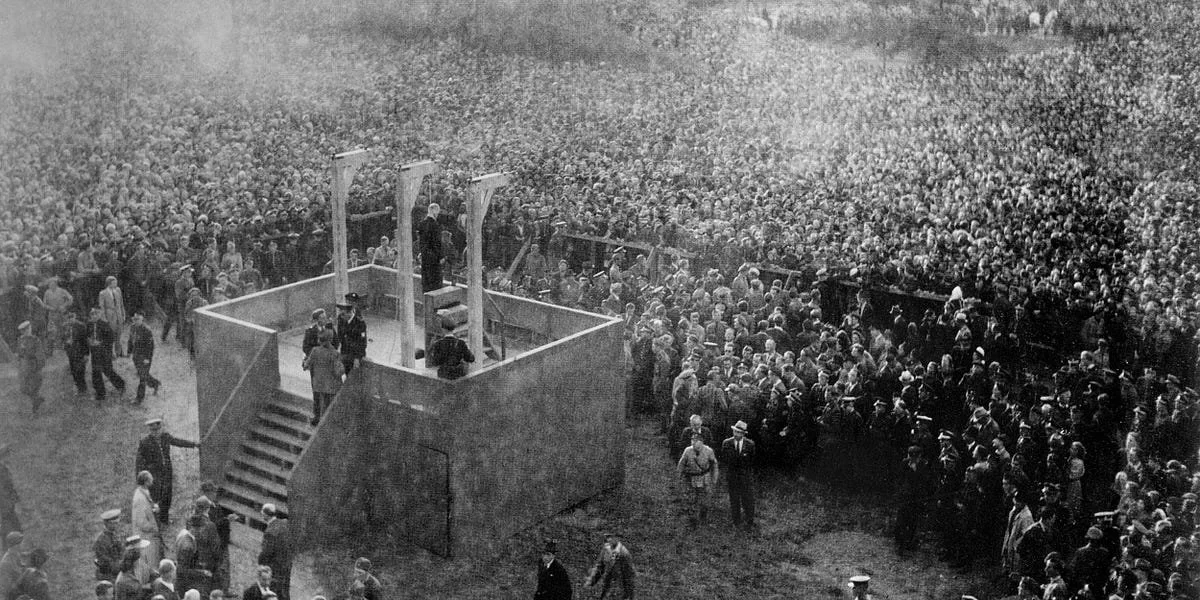

“The scaffold, indeed, when it is prepared and set up, has the effect of a hallucination. We may be indifferent to the death penalty, and may not declare ourselves, yes or no, so long as we have not seen a guillotine with our own eyes. But when we see one, the shock is violent, and we are compelled to decide and take part, for or against. Some admire it, like Le Maistre; others execrate it, like Beccaria. The guillotine is the concretion of the law; it is called the Avenger; it is not neutral and does not permit you to remain neutral. He who sees it quakes with the most mysterious of tremblings. All social questions set up their points of interrogation about this axe. The scaffold is vision. The scaffold is not a mere frame, the scaffold is not a machine, the scaffold is not an inert piece of mechanism made of wood, of iron, and of ropes. It seems a sort of being which had some sombre origin of which we can have no idea ; one would say that this frame sees, that this machine understands, that this mechanism comprehends ; that this wood, this iron, and these ropes, have a will. In the fearful reverie into which its presence casts the soul, the awful apparition of the scaffold confounds itself with its horrid work. The scaffold becomes the accomplice of the executioner; it devours, it eats flesh, and it drinks blood. The scaffold is a sort of monster created by the judge and the workman, a spectre which seems to live with a kind of unspeakable life, drawn from all the death which it has wrought.”

“’Madame Magloire,’ replied the bishop, ‘you are mistaken. The beautiful is as useful as the useful.’ He added after a moment’s silence, ‘Perhaps more so.’”

“A saint who is addicted to abnegation is a dangerous neighbour; he is very likely to communicate to you by contagion an incurable poverty, an anchylosis of the articulations necessary to advancement, and, in fact, more renunciation than you would like; and men flee from this contagious virtue. Hence the isolation of Monseigneur Bienvenu. We live in a sad society. Succeed; that is the advice which falls, drop by drop, from the overhanging corruption.”

“What was more needed by this old man who divided the leisure hours of his life, where he had so little leisure, between gardening in the day time, and contemplation at night? Was not this narrow inclosure, with the sky for a background, enough to enable him to adore God in his most beautiful as well as in his most sublime works? Indeed, is not that all, and what more can be desired? A little garden to walk, and immensity to reflect upon. At his feet something to cultivate and gather; above his head something to study and meditate upon; a few flowers on the earth, and all the stars in the sky.”

“Here we must again ask those questions, which we have already proposed elsewhere: was some confused shadow of all this formed in his mind. Certainly, misfortune, we have said, draws out the intelligence; it is doubtful, however, if Jean Valjean was in a condition to discern all that we here point out. If these ideas occurred to him, he but caught a glimpse, he did not see; and the only effect was to throw him into an inexpressible and distressing confusion. Being just out of that misshapen and gloomy thing which is called the galleys, the bishop had hurt his soul, as a too vivid light would have hurt his eyes on coming out of the dark. The future life, the possible life that was offered to him thenceforth, all pure and radiant, filled him with trembling and anxiety. He no longer knew really where he was. Like an owl who should see the sun suddenly rise, the convict had been dazzled and blinded by virtue.

One thing was certain, nor did he himself doubt it, that he was no longer the same man, that all was changed in him, that it was no longer in his power to prevent the bishop from having talked to him and having touched him.

….

While he wept, the light grew brighter and brighter in his mind — an extraordinary light, a light at once transporting and terrible. His past life, his first offence, his long expiation, his brutal exterior, his hardened interior, his release made glad by so many schemes of vengeance, what had happened to him at the bishop's, his last action, this theft of forty sous from a child, a crime meaner and the more monstrous that it came after the bishop's pardon, all this returned and appeared to him, clearly, but in a light that he had never seen before. He beheld his life, and it seemed to him horrible; his soul, and it seemed to him frightful. There was, however, a softened light upon that life and upon that soul. It seemed to him that he was looking upon Satan by the light of Paradise.”

“They were of those dwarfish natures, which, if perchance heated by some sullen fire, easily become monstrous. The woman was at heart a brute; the man a blackguard: both in the highest degree capable of that hideous species of progress which can be made towards evil. There are souls which, crablike, crawl continually towards darkness, going back in life rather than advancing in it; using what experience they have to increase their deformity; growing worse without ceasing, and becoming steeped more and more thoroughly in an intensifying wickedness. Such souls were this man and this woman.”

“Some people are malicious from the mere necessity of talking. Their conversation, tattling in the drawing-room, gossip in the ante-chamber, is like those fireplaces that use up wood rapidly; they need a great deal of fuel; the fuel is their neighbour.”

“There are many of these virtues in low places; some day they will be on high. This life has a morrow.”

“Must he denounce himself? Must he be silent? He could see nothing distinctly. The vague forms of all the reasonings thrown out by his mind trembled, and were dissipated one after another in smoke. But this much he felt, that by whichever resolve he might abide, necessarily, and without possibility of escape, something of himself would surely die; that he was entering into a sepulchre on the right hand, as well as on the left; that he was suffering a death-agony, the death-agony of his happiness, or the death-agony of his virtue.

Alas! all his irresolutions were again upon him. He was no further advanced than when he began.

So struggled beneath its anguish this unhappy soul. Eighteen hundred years before this unfortunate man, the mysterious Being, in whom are aggregated all the sanctities and all the sufferings of humanity, He also, while the olive trees were shivering in the fierce breath of the Infinite, had long put away from his hand the fearful chalice that appeared before him, dripping with shadow and running over with darkness, in the star-filled depths.”

“Probity, sincerity, candour, conviction, the idea of duty, are things which, mistaken, may become hideous, but which, even though hideous, remain great; their majesty, peculiar to the human conscience, continues in all their horror; they are virtues with a single vice— error. The pitiless, sincere joy of a fanatic in an act of atrocity preserves an indescribably mournful radiance which inspires us with veneration. Without suspecting it, Javert, in his fear-inspiring happiness, was pitiable, like every ignorant man who wins a triumph. Nothing could be more painful and terrible than this face, which revealed what we may call all the evil of good.”

“This light of history is pitiless; it has this strange and divine quality that, all luminous as it is, and precisely because it is luminous, it often casts a shadow just where we saw a radiance; of the same man it makes two different phantoms, and the one attacks and punishes the other, and the darkness of the despot struggles with the splendour of the captain. Hence results a truer measure in the final judgment of the nations. Babylon violated lessens Alexander; Rome enslaved lessens Caesar; massacred Jerusalem lessens Titus. Tyranny follows the tyrant. It is woe to a man to leave behind him a shadow which has his form.”

“A certain amount of tempest always mingles with a battle. Quid obscurum, quid divinum. Each historian traces the particular lineament which pleases him in this hurly-burly. Whatever may be the combinations of the generals, the shock of armed masses has incalculable recoils in action, the two plans of the two leaders enter into each other, and are disarranged by each other. Such a point of the battle-field swallows up more combatants than such another, as the more or less spongy soil drinks up water thrown upon it faster or slower. You are obliged to pour out more soldiers there than you thought. An unforeseen expenditure. The line of battle waves and twists like a thread; streams of blood flow regardless of logic; the fronts of the armies undulate; regiments entering or retiring make capes and gulfs; all these shoals are continually swaying back and forth before each other; where infantry was, artillery comes; where artillery was, cavalry rushes up; battalions are smoke. There was something there; look for it; it is gone; the vistas are displaced; the sombre folds advance and recoil; a kind of sepulchral wind pushes forwards, crowds back, swells and disperses these tragic multitudes. What is a hand to hand fight? an oscillation. A rigid mathematical plan tells the story of a minute, and not a day. To paint a battle needs those mighty painters who have chaos in their touch. Rembrandt is better than Vandermeulen. Vandermeulen, exact at noon, lies at three o’clock. Geometry deceives; the hurricane alone is true. This is what gives Folard the right to contradict. Polybius. We must add that there is always a certain moment when the battle degenerates into a combat, particularises itself, scatters into innumerable details, which, to borrow the expression of Napoleon himself, ‘'belong rather to the biography of the regiments than to the history of the army.” The historian, in this case, evidently has the right of abridgment. He can only seize upon the principal outlines of the struggle, and it is given to no narrator, however conscientious he may be, to fix absolutely the form of this horrible cloud which is called a battle.”

“Was it possible that Napoleon should win this battle? We answer no. Why? Because of Wellington? Because of Blucher? No. Because of God.

For Bonaparte to be conqueror at Waterloo was not in the law of the nineteenth century. Another series of facts were preparing in which Napoleon had no place. The ill-will of events had long been announced.

It was time that this vast man should fall.

The excessive weight of this man in human destiny disturbed the equilibrium. This individual counted, of himself alone, more than the universe besides. These plethoras of all human vitality concentrated in a single head, the world mounting to the brain of one man, would be fatal to civilisation if they should endure. The moment had come for Incorruptible supreme equity to look to it. Probably the principles and elements upon which regular gravitations in the moral order as well as in the material depend, began to murmur. Reeking blood, overcrowded cemeteries, weeping mothers — these are formidable pleaders. When the earth is suffering from a surcharge, there are mysterious moanings from the deeps which the heavens hear.

Napoleon had been impeached before the Infinite, and his fall was decreed.

He vexed God.

Waterloo is not a battle; it is the change of front of the universe.”

“He felt in this a pre-ordination from on high, a volition of some one more than man, and he would lose himself in reverie. Good thoughts as well as bad have their abysses.”

“In the nineteenth century the religious idea is undergoing a crisis. We are unlearning certain things, and we do well, provided that while unlearning one thing we are learning another. No vacuum in the human heart! Certain forms are torn down, and it is well that they should be, but on condition that they are followed by reconstructions.”

“To be ultra is to go beyond. It is to attack the sceptre in the name of the throne, and the mitre in the name of the altar; it is to maltreat the thing you support; it is to kick in the traces; it is to cavil at the stake for undercooking heretics; it is to reproach the idol with a lack of idolatry; it is to insult by excess of respect; it is to find in the pope too little papistry, in the king too little royalty, and too much light in the night; it is to be dissatisfied with the albatross, with snow, with the swan, and the lily in the name of whiteness; it is to be the partisan of things of the point of becoming their enemy; it is to be so very pro, that you are con.”

“That evening left Marius in a profound agitation, with a sorrowful darkness in his soul. He was experiencing what perhaps the earth experiences at the moment when it is furrowed with the share that the grains of wheat may be sown; it feels the wound alone; the thrill of the germ and the joy of the fruit do not come until later.”

“M. Mabeuf’s political opinion was a passionate fondness for plants, and a still greater one for books. He had, like everybody else, his termination in ist, without which nobody could have lived in those times, but he was neither a royalist, nor a Bonapartist, nor a chartist, nor an Orleanist, nor an anarchist; he was an old-bookist.”

“There is under the social structure, this complex wonder of a mighty burrow, — of excavations of every kind. There is the religious mine, the philosophic mine, the political mine, the economic mine, the revolutionary mine. This pick with an idea, that pick with a figure, the other pick with a vengeance. They call and they answer from one catacomb to another. Utopias travel under ground in the passages. They branch out in every direction. They sometimes meet there and fraternize. Jean Jacques lends his pick to Diogenes, who lends him his lantern. Sometimes they fight. Calvin takes Socinius by the hair. But nothing checks or interrupts the tension of all these energies towards their object. The vast simultaneous activity, which goes to and fro, and up and down, and up again, in these dusky regions, and which slowly transforms the upper through the lower, and the outer through the inner; vast unknown swarming of workers. Society has hardly a suspicion of this work of undermining which, without touching its surface, changes its substance. So many subterranean degrees, so many differing labours, so many varying excavations. What comes from all this deep delving? The future.”

“There has been an attempt, an erroneous one, to make a special class of the bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie is simply the contented portion of the people. The bourgeois is the man who has now time to sit down. A chair is not a caste.”

“All the problems which the socialists propounded, aside from the cosmogonic visions, dreams, and mysticism, may be reduced to two principal problems.

First problem:

To produce wealth.

Second problem:

To distribute it.

The first problem contains the question of labour.

The second contains the question of wages.

In the first problem the question is of the employment of force.

In the second of the distribution of enjoyment.

From the good employment of force results public power.

From the good distribution of enjoyment results individual happiness.

By good distribution, we must understand not equal distribution, but equitable distribution. The highest equality is equity.

From these two things combined, public power without, individual happiness within, results social prosperity.

Social prosperity means, man happy, the citizen free, the nation great.

England solves the first of these two problems. She creates wealth wonderfully; she distributes it badly. This solution, which is complete only on one side, leads her inevitably to these two extremes: monstrous opulence, monstrous misery. All the enjoyment to a few, all the privation to the rest, that is to say, to the people; privilege, exception, monopoly, feudality, springing from labour itself; a false and dangerous situation which founds public power upon private misery, which plants the grandeur of the state in the suffering of the individual. A grandeur ill constituted, in which all the material elements are combined, and into which no moral element enters.

Communism and agarian law think they have solved the second problem. They are mistaken. Their distribution kills production. Equal partition abolishes emulation. And consequently labour. It is a distribution made by the butcher, who kills what he divides. It is therefore impossible to stop at these professed solutions. To kill wealth is not to distribute it.

The two problems must be solved together to be well solved. The two solutions must be combined and form but one.

Solve the first only of the two problems, you will he Venice, you will be England. You will have like Venice an artificial power, or like England a material power; you will be the evil rich man, you will perish by violence, as Venice died, or by bankruptcy, as England will fall, and the world will let you die and fall, because the world lets everything fall and die which is nothing but selfishness, everything which does not represent a virtue or an idea for the human race.

It is of course understood that by these words, Venice, England, we designate not the people, but the social constructions; the oligarchies superimposed upon the nations, and not the nations themselves. The nations always have our respect and our sympathy. Venice, the people, will be reborn; England, the aristocracy, will fall, but England, the nation, is immortal. This said, we proceed.

Solve the two problems, encourage the rich, and protect the poor, suppress misery, put an end to the unjust speculation upon the weak by the strong, put a bridle upon the iniquitous jealousy of him who is on the road, against him who has reached his end, adjust mathematically and fraternally wages to labour, join gratuitous and obligatory instruction to the growth of childhood, and make science the basis of manhood, develop the intelligence while you occupy the arm, be at once a powerful people and a family of happy men, democratise property, not by abolishing it, but by universalising it, in such a way that every citizen without exception may be a proprietor, an easier thing than it is believed to be; in two words, learn to produce wealth and learn to distribute it, and you shall have material grandeur and moral grandeur combined; and you shall be worthy to call yourselves France.”

“Nothing is really small; whoever is open to the deep penetration of nature knows this. Although indeed no absolute satisfaction may be vouchsafed to philosophy, no more in circumscribing the cause than in limiting the effect, the contemplator falls into unfathomable ecstasies in view of all these decompositions of forces resulting in unity. All works for all.”

“The future belongs still more to the heart than to the mind. To love is the only thing which can occupy and fill up eternity. The infinite requires the inexhaustible.”

“Civil war? What does this mean? Is there any foreign war? Is not every war between men, war between brothers? War is modified only by its aim. There is neither foreign war, nor civil war; there is only unjust war and just war.”

“His supreme anguish was the loss of all certainty. He felt that he was uprooted. The code was now but a stump in his hand. He had to do with scruples of an unknown species. There was in him a revelation of feeling entirely distinct from the declarations of the law, his only standard hitherto. To retain his old virtue, that no longer sufficed. An entire order of unexpected facts arose and subjugated him. An entire new world appeared to his soul; favour accepted and returned, devotion, compassion, indulgence, acts of violence committed by pity upon austerity, respect of persons, no more final condemnation, no more damnation, the possibility of a tear in the eye of the law, a mysterious justice according to God going counter to justice according to men. He perceived in the darkness the fearful rising of an unknown moral sun; he was horrified and blinded by it. An owl compelled to an eagle’s gaze.

He said to himself that it was true then, that there were exceptions, that authority might be put out of countenance, that rule might stop short before a fact, that everything was not framed in the text of the code, that the unforeseen would be obeyed, that the virtue of a convict might spread a snare for the virtue of a functionary, that the monstrous might be divine, that destiny had such ambuscades as these, and he thought with despair that even he had not been proof against a surprise.

He was compelled to recognise the existence of kindness. This convict had been kind. And he himself, wonderful to tell, he had just been kind. Therefore he had become depraved.”

The Only Way Out

I know that I am unwell; I know that there is nothing good in me, apart from Christ. And I do not feel very Christian in spirit today.

Yesterday, on the anniversary of the President’s attempt to violently suppress the will of the electorate, which killed several innocents, the White House proudly published a bald-faced lie, promulgating a false version of events that we all should remember. But they knew that their supporters don’t care anyway. Then, today, a protester, a single mother, was shot and killed by an ICE agent during a confrontation. Footage of the incident suggests that both parties may have made mistakes; but regardless of what happened in the confusion of the moment, which is still being debated while we wait for more evidence to emerge, the fact remains that the agent was on that street as part of what has for months been a gang of political thugs who have repeatedly committed illegal violence against the innocent, and faced no repercussions for doing so, who in many cases have no qualifications and no legitimate authority to hold deadly force over any citizen, and who conceal their identities, so that they must all be treated as one. The woman who died was there trying to resist, in some small way, this visitation of evil upon her community. The Department of Homeland Security has wasted no time in posthumously declaring her a terrorist, slandering her in order to justify the killing and absolve themselves of guilt for a situation entirely of their own making. And again, they do this because they are confident that their supporters do not care, and that nothing will happen to them.

I have spent too much time already on my phone, distracted from living by the addiction to wrath, and witnessing over and over and over the shameless and open embrace of evil by many who mock and laugh at the death of the innocent at the hands of their fellow tribesmen. And I know better than to condemn others, not just because I am also guilty, and not just because my motives are not the pure love of justice, but also the forbidden, dramatic burn of spiteful rage, and the self-flattery of pride seizing upon a moment when I feel myself to be so right that going too far seems justified. And I know I am casting about in this moment, simply the latest addition to a long train of wrongs, for some as of yet unshattered glass to break in case of fire, some new word to utter, to respond to the worsening world by escalating in turn and making myself unmistakably clear, as if a word could be said which would cause the wicked to combust, rather than simply being laughed off, or silently ignored. And that is itself an almost comically delusional self-important way of thinking, the shame of which alone should be enough to shut me up. And yet I want to say this one thing, and then because of that I must say another.

One

I will be simple. This opinion did not form in a day, or in response to a single day’s events; it accreted through the friction of many actions taken in the same direction for ten years, until it has, finally, accumulated a weight which can no longer be supported. There are so many things this administration has done, continues to do, and threatens to begin, which constitute crimes against humanity. There is no point rehearsing everything that has happened. It is enough to state the simplest, most important realities.

They imprison, injure, rape, and kill innocents.

They proudly admit their motives are selfish and cruel.

They spurn legal accountability and lie to protect themselves.

They cannot be shamed into stopping.

We cannot bring justice in any true sense; we are not permitted revenge. The rectification of evil is the province of God and waits beyond time for its fulfillment. But when such things are done, the guilty must be stopped, and when the guilty are society’s leaders, backed by a large portion of public opinion, and their crimes cause as much harm to the innocent as these do, then a demonstration must be made for future leaders and publics yet unborn that neither the elite nor the majority are so practically immune from accountability that they believe themselves to be beyond good and evil. The lesson must be scored into history so that it will not soon be forgotten and cannot be misinterpreted. There is one tool which we have availed ourselves of for this purpose, and which today would loom above ordinary justice.

We must hang them from the gallows.

Two

We must decide to hang them; and then we must let them live instead.

Nothing we can do will surely deter the atrocities of future generations. Nothing we can do will restore the dead or repair the harm done. At the end of our brief day, the only thing we can do is live as Christ would. And Christ affirms the necessity of the gallows, that the irreparable breach of death is the only answer to the irreparable harm of evil. But he affirmed it by going to the gallows Himself, the once for all. We have no right to erect another. And then He made a demonstration for all time that the harm of death is not, in fact, irreparable; and so the harm of evil is in the same way no longer irreparable. Mercy, then, is justice; we witness that God has done justice in death, and will do justice by undoing all malice, all injury, all kidnapping, all rape, all murder, until every spot of blood is both accounted for and also restored to living veins. Then the only retribution will be restitution.

These are my conclusions. We cannot arrive at the second except by way of the first; we cannot achieve any kind of justice by settling on the first, or we remain trapped in the hell we started in.

Music in July 2025

Belated, but I have been traveling all December. Here are my songs from last July:

Yes, I have now discovered Meat Loaf, too operatic and big to deny.

Cousin Tony’s Brand New Firebird continues to deliver the strange, smooth, peaceful goods with their album Rosewater Crocodile.

I have also discovered the hurdy gurdy as an instrument, and I think we should deploy it more often.

I can’t believe I didn’t get into Texas sooner, it’s very much the kind of music I enjoy.

Mother Big River sure is a ponder.

Alex G’s Headlights and Frightened Rabbit’s The Midnight Organ Fight are two excellent, odd albums.

I can’t stop playing You Can Call Me Al over and over again in my head.

Hideaway has some of my favorite sentimentalism from The Weepies.

Music in June 2025

The score to Sally Potter’s 1992 Virginia Woolf adaptation Orlando is exuberant and exultant and I love it.

The nice thing about artists like Reol is I can put them on when I want loud shouty music, but not in English, because that would distract from my work.

Modern English is a favorite of mine, and Let’s All Dream is a good reminder to “get back to being human.”

All Day Long has a wonderful bridge that just glows and shimmers.

There’s a strangely contented yearning at the core of most of Humbert Humbert’s work that makes it irreplaceable.

Oats We Sow is a beautiful expression of the tragedy of our own hearts.

Take It on Faith has such an aggressive melody, and it makes me want to move back to the Southwest.

I am just discovering Rilo Kiley, and I’m kind of surprised I didn’t sooner, given how much I like it.

Of course The Beths are back on my playlist, but they aren’t the only artist from down under – Montaigne put out the wonderful album it’s hard to be a fish this year.

I’m not sure I can explain why Beth’s Farm is so affecting for being such an odd song, but it is.

Everybody Laughs is a wonderful way to respond playfully to life.

2024 Photos

Here is my selected album of photos to highlight from 2024. I’ll post them all on Instagram individually over the next little while, but this is a better resolution: https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjCA5QB

UCONN Medieval Studies, 1969-2025

The University of Connecticut formally shuttered its longstanding graduate program in Medieval Studies earlier this year. This news is not recent; it took several months to find its way to me, now living at some remove from both academic and Connecticut goings-on, and then yet more months elapsed after I had meant to comment on it, only for that note to languish on my to-do list. Neither is it terribly surprising—when I was in the program, I recall feeling as though the barbarians were already at the academic gates, though I still feel this as a shock coming so soon after I left the program in the summer of 2019. It is a hard thing to outlive institutions you hoped would be a legacy for future students in the same way they were a legacy to you. It is particularly hard when that institution is itself an endangered species.

When I graduated college in 2013, my whole ambition was to become a tweed-clad professor in imitation of Tolkien; as silly as that may sound, I could imagine no higher station. I knew that I wanted a doctorate in literature, and that I was most interested in early medieval mythology, but I had scant historical and no linguistic background in the period. So, as a first step, I began casting about for a place to earn a period-specific master’s degree. As it happens, there are very few places where one can do this in North America. Most of the programs with such degrees are in Britain, and while I tried to get into these, I was never going to realistically get the financial support I would need to attend. So, as I went through multiple rounds of applications over several years, my focus narrowed to the three North American programs offering some kind of medieval studies master’s: the University of Toronto, Western Michigan University, and UCONN.

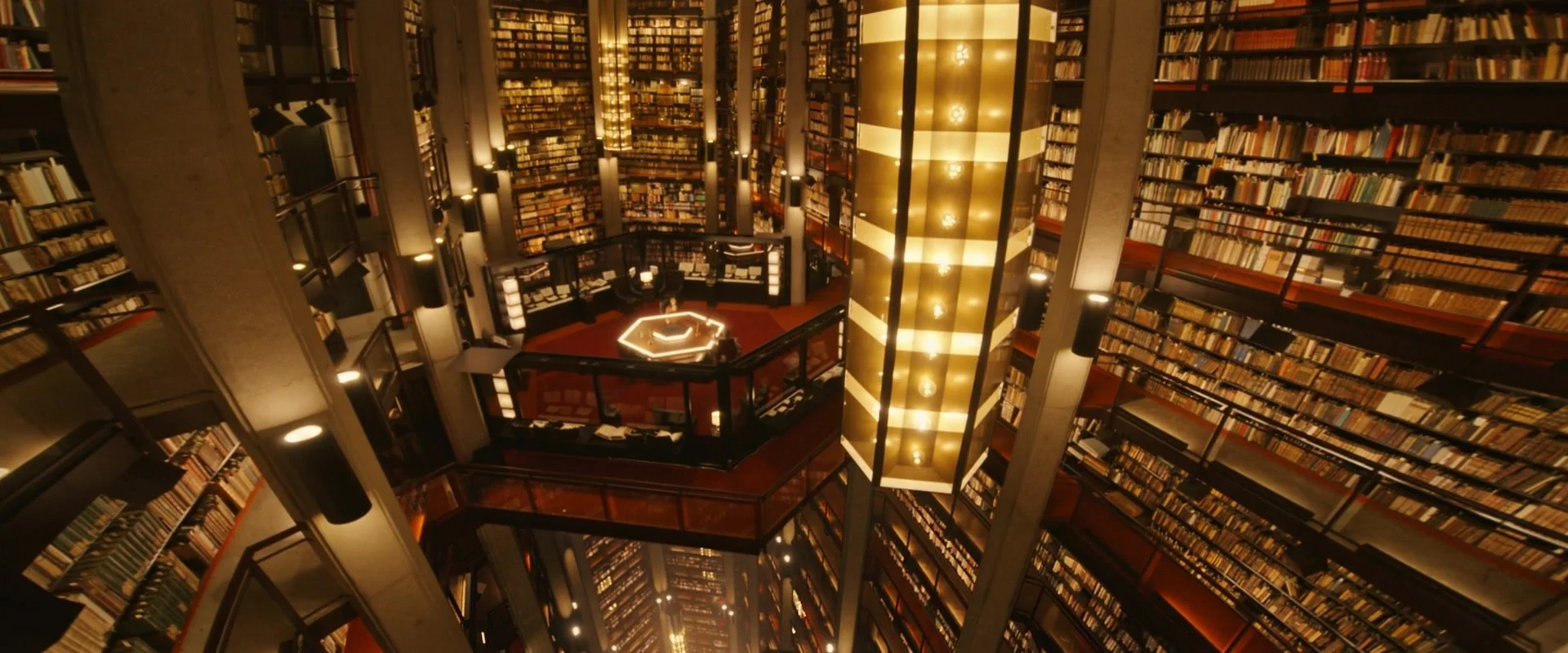

I am a strange person to eulogize the medieval studies program at UCONN, because I was only there for two years, unlike so many others, and because it provided the context in which I decided to give up my pursuit of an academic dream. But this is no poor reflection on the program—my advisors and peers were a model academic community, and that included the openness and honesty that allowed me the space to reflect on the limits of my ambition, and my actual priorities in life, without judgment or expectation. And I did not want to leave academia; in fact, I greatly miss it, though I am happier in my current situation than I ever expected to be. Now I will miss the medieval studies program as well, where for two delightful years I learned so much, including being humbled from time to time, and felt such warmth in the community, not just of medievalists, but of the whole English Department. When I think of my time at UCONN, it is of evenings at the homes of sages; long, quiet days in our cloistered library that served as office; and classes in the history building that where only myself, my colleague, and my professor, digging through a book.

There were precious few medieval studies programs in the world to begin with; now there is one less. I could rail at the decline of the field, or worry over the future of learning, as I do often enough; but what will that do? I am just grateful to have been there while I still could.

Music in May 2025

Vashti Bunyan is a delightful voice I hadn’t heard before.

Both Sides Now in any form brings one to the verge of tears.

There’s a whole slew of fun, punchy songs I can’t really categorize.

Every Day Like the Last resolves into a kind of hopefully grim mantra.

Bruno Coulais’ excellent score for Wolfwalkers is a great advertisement for a very good film.

Regina Spektor’s 2009 Far and Stars’ 2007 In Our Bedroom After the War are both wonderfully sentimental miscreations of the late aughts.

Chapterhouse is a great purveyor of that lovely fuzz that characterized so much of the end of the Cold War.

I keep returning to Australian melancholy; there is something in me that longs for the dust, I suppose. What can I say? It smells nice there.

Joan Baez is an encouragement in these strange days.

Music in April 2025

The main thing of note in my April 2025 playlist is the prominent inclusion of Dylan, but even moreso, of Joan Baez—between the two of them the greatest American songwriter and the greatest American musical artist. Very little else approaches the holy mountain of emotion their work conjures.

Neko Case’s 2009 album Middle Cyclone is worth hearing in full, but especially the fencepost-ripping This Tornado Loves You.

Pulling on a Line’s key lyric, “and sometimes it pulls on me,” is strangely encouraging to bring to mind sometimes.

Patience, Moonbeam, Great Grandpa’s newest album, is an elevation of their work into a realm more mellow and melancholy than before.

Luke & Leanna doesn’t feel like the kind of ballad that you’d expect from 2025—it harkens back to about forty years ago, and that’s great.

Where We Are, Where We Go

1. Truth Demands Freedom of Speech

American civic religion is a strange thing; we take our own founding documents and the myths they construct perhaps more seriously than any other country (though the French might disagree). Perhaps this is inescapable in a revolutionary state—if you had to justify unsanctioned violence against the established government in order to found your country, the justifications given tend to assume a sacrosanct quality, because to question them would be to open a chasm of guilt and instability that might threaten the entire national identity. This should commend us to a healthy skepticism of our own founding myths in a philosophical vacuum. But as I have learned from extensive personal experience, intellectual and moral self-doubt beyond a certain point devours itself with no benefit to show for all its questioning. There are some positive truths and moral principles, and there is value in standing for the right as we see the right, as long as we remember we cannot see all.

In that spirit (or excuse, if you’re cynical), I submit that Declaration of Independence’s arrogation of self-evidence to the existence of basic rights and freedoms is perhaps the most defensible act of rhetorical hubris committed to parchment. The claim that some moral rule is self-evidently true, even if unsubstantiated, is an appeal to the existence Truth itself. Whether or not God’s Truth which undergirds the universe extends to questions of taxation without representation, the existence of an ultimate moral standard—something all humans instinctively know exists—is itself the guarantee of at least one right: the right to the Truth. The obligation to believe and speak the truth, as it is, not as socially-determined, demands each soul believe and speak truly. In a world ruled by imperfect men, this carries as corollary the necessary right to speak freely, lest we set ourselves up in judgment as pretenders to divinity. Factual or not, all speech which is not free, all speech which is coerced, is a lie, and can have nothing to do with the Truth.

2. Truth Must Name Injustice

It is no accident that scripture is filled with prophets speaking truth to worldly powers and protesting injustices—because God’s love cannot abide injustice, and the beginning of any rectification is the light of truth. We must recognize what is wrong, and we must name it, before we can have any hope of attaining what should be. This is why so much of the active language describing how Christians should further the Kingdom amounts to verbs of communication—testifying, witnessing, confessing.

Many of the Christians who have been reluctant to speak to the injustices of the current administration hold political views motivated by their own allegiance to truth and abhorrence for injustice. They would argue that abortion is a grave injustice (I would agree, though we may differ on the question of how society should respond, what the root of the injustice is, and what the potential complications of social policy); they might also argue that ideas now in vogue about gender identity and sexuality have created subtler injustices, unintended, against children or against one’s own well-being (I would also generally agree, though again we may differ in some details and on how to respond socially). I don’t think these issues, in the context of the politics of the past ten years, justified putting Donald Trump in power; many obviously disagree. We’re not going to resolve that difference now.

What we should all be able to do is name the violence done to suspected illegal immigrants, peaceful protesters, and political opponents for the inexcusable injustice that it is. I know those to my right may ask why I emphasize this and minimize what they consider more important: obviously, we have different understandings of the salience of the issues. Or perhaps they are right, and I am simply mistaken or, worse, biased out of a preference for some sins over others, or due to social pressure. If that is the case, then it is a moral problem—for me. It does not remove the responsibility from you to object to injustice, even if you think I am hypocritical or blind. In fact, if you voted for this administration or for the members of Congress who have enabled everything about it by their consistent abdication of responsibility, then you are more obligated to speak to these injustices than to any other—especially since these are wholly unnecessary harms actively committed by the state.

3. The President is Injuring Innocents

I will never be able to compile every incident and story that indicts this administration’s conduct as well beyond the pale of basic, nonpartisan right and wrong. I adjure you to read the newspaper and listen to the victims. I will simply remind you of a few things I have already noted.

The President began by abruptly cutting off aid that cost a pittance to maintain, failed to save money by doing so, and in the process left millions of our neighbors around the world to starve and sicken and die. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/03/15/opinion/foreign-aid-cuts-impact.html https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2025/02/usaid-dismantle-trump-damage/681644/ https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2025/04/usaid-doge-children-starvation/682484/ https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2025/03/diseases-doge-trump/681964/ https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/02/health/usaid-cuts-deaths-infections.html https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2025/02/usaid-doge-dismantle-cost-foreign-aid/681573/ https://www.impactcounter.com/dashboard?view=table&sort=interval_minutes&order=asc https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/10/opinion/pro-life-foreign-aid-pepfar.html https://www.propublica.org/article/trump-usaid-malawi-state-department-crime-sexual-violence-trafficking

The President used ICE to seize people, in some cases illegally or even taking the wrong person by mistake, and send them without a lawyer or a phone call to a foreign prison where they were tortured, and, when ordered to return people mistakenly sent there, the President said that he would not do so—ever. https://www.andrewroosbell.com/blog/you-are-hurting-people

The President continues to use ICE not simply to detain and deport illegal immigrants according to the normal process of law, but to terrorize harmless contributors to society, punish children for things they were not responsible for, betray our veterans, abuse and neglect prisoners, and to do all this to anyone who fits a profile—a discriminatory, racist profile—including legal immigrants and American citizens. https://www.andrewroosbell.com/blog/the-tip-of-the-iceberg

4. The President is Trying to Silence the Truth

The President has made it abundantly clear, both in numerous statements made by himself and members of his administration, that his goal is to punish people and institutions for criticizing him. This is not mere hot air from a blowhard: from the beginning of this year the administration has persistently experimented with new ways to impose a high cost on speech against the President and his policy agenda. This includes singling out foreign students, here legally on student visas, arresting, and trying to deport them because of their political activism, or even for writing an op-ed. It has extended to suborning federal funding as a cudgel to pressure universities into policing their students’ and faculty’s speech on behalf of the administration, using regulatory oversight of mergers to pressure large media corporations into taking a more accommodating tack in their coverage, or even firing an (unaccountably) popular late-night host. Increasingly it takes the form of legal persecution from the Department of Justice, which has taken to firing everyone from federal prosecutors to FBI agents if they will not help the President prosecute his political enemies on ginned-up charges, not out of any scruple for justice, but to intimidate others into silence, or simply as a matter of petty resentment.

5. The Forum for Truth is Protest

Meanwhile, for people who do not possess a large enough platform to have their job targeted, or who do not occupy a position of prominence that might invite prioritization for a specious prosecution, the best way to speak is as the people, in large, peaceful protests. Ordinary individuals may not command much attention on their own, but a large group of people motivated enough to take time out of their busy day to protest something in a coordinated fashion signals a breadth of opposition that is harder to hide. Naturally, protests tend to spring up around ICE facilities and operations, as people are rightly outraged by thugs kidnapping people off the streets with excessive force and a substantial degree of malice and racial animus. And ICE increasingly has chosen to attack protesters physically, shooting them in the head with rubber bullets, gas, driving into crowds, beating people, pointing guns at people who are simply filming them, and detaining people as a punishment, whose only crime was holding a sign and speaking out. ICE is increasingly an organization recruited from the ranks of people with a grudge against immigrants and liberals and who seem prone to aggression and woefully under-trained for law enforcement. When these people are placed in an us-versus-them scenario with citizen protesters who are angry at the outrageous acts they are committing, spontaneous eruptions of violence are not surprising—and that is not a justification in any way for federal agents to commit violence, especially in situations of their own making. But there is also a calculated side to the intimidation: the administration clearly wants to frame all protesters as violent rebels and to provoke violence in order to justify a repressive military crackdown.

Over the course of the past couple of weeks, I have seen senior administration officials and allies roll out the accusation that the participants in the No Kings series of protests specifically are domestic terrorists. This would be a laughable statement, if it did not carry with it a threat that is not in the least bit funny. There have already been numerous No Kings protests across the country during the course of the administration. They were by and large peaceful and well-organized. I attended a couple here in Anchorage, pictured below, and they had a character of a festival.

There were as many middle-class suburban grandmothers as there were college students, as many families with young children in tow waving flags as keffiyeh-draped activists. Police looked on placidly and passing cars honked in support. But the President calls all of those who participated – the grandmothers, the schoolteachers, the children, and yours truly—domestic terrorists. There’s a simple reason for this. The President is more unpopular than ever, the population more upset by footage of ICE raids and violence against protesters, and there is another No Kings protest scheduled for this Saturday, October 18, all over the country. This matters, because this protest has been the kind that large numbers of ordinary engaged voters with jobs and families show up to. The President is using the term domestic terrorist specifically to create a flimsy justification to send men with guns to break up these coming peaceful protests, and to explain in advance any violence these men do. There are two goals: to create violent clashes which can be used to excuse ruling by force, and to make ordinary people think twice about showing up to protest, for fear they might get hurt or get in trouble.

6. Where We Go

This is why I need you to show up on Saturday—because the President has already issued this threat in an attempt to scare people out of speaking publicly against him. In such a moment, staying home out of a desire to stay out of trouble (an impulse I well understand—I am not really a protest person, as I said to a friend as I traipsed along awkwardly after a bunch of marchers I did not particularly like or trust) is a form of surrender. I understand not everyone can show up. But to stay away because of a concern that things might go south is, in this context, a forfeiture of the right to free speech, and a betrayal of that right for others. The President is counting on people staying home so the crowds will be smaller, easier to suppress, and more radical. He is also counting on those who do show up to engage in violence. In this scenario, there is but one narrow way through: we must neither stay home, nor engage in violence.

You can find the protest closest to you on this site: https://www.nokings.org/ As you can see from the map, there should be a protest within reach of you. The one in Anchorage is at 3:00 PM on Saturday in Town Square Park.

I want to say one more thing, specifically for those who do not feel they ideologically align with these protests, either because they tend to be dominated by radicals, or because you are a conservative Republican. I completely understand being put off by the opinions, attitudes, and aesthetics of many protesters, or being concerned that some will cause trouble. At the protests I’ve attended, I’ve seen a lot of signs I wouldn’t personally wave. The last one featured a speaker before the march who slid right into tankie anti-western-imperialism rhetoric, essentially blaming NATO and capitalism for Russian aggression in Ukraine. As someone who enjoys watching both my 401K grow and NATO fancam edits on youtube, and who thinks that sort of ideology amounts to supporting a genocide in eastern Ukraine, I could not disagree more, and I was extremely upset in that moment—needless to say, I did not clap. But then we marched, and the march was against the administration’s authoritarianism. And that’s the thing—at any large protest, the organizers will often be radicals who one may vehemently disagree with; but everyone should be able to come together, only responsible for what we individually say, to send a collective signal of opposition.

That brings me to conservatives and those who might even support much of the administration’s policy. I’m not going to try to debate federal policy or ideology with you, I assume that you, like me, have considered your views at great length and have strong and settled reasons for believing what you believe. But if you are an American and you care about liberty, then presumably you care about freedom of speech. This administration is currently attempting to suppress and intimidate until that right is reduced to words on parchment in the National Archives, with no actual force in American life. Even if you agree with the President on other issues, you should want to let him know that suppressing criticism is a bridge too far even for his supporters. There’s room for you at the march. I’d love to see you there.

Music in March 2025

Highlights from my March 2025 playlist.

Stars has quickly established itself as one of my favorite bands.

Redemption Arc and Light Through the Linen are both achingly hopeful in small ways.

Cameron Winter’s Love Takes Miles is a whole word.

Adrianne Lenker is only capable of writing interesting songs, and her album from last year is no exception.

Della Loved Steve was an album I kept in constant rotation for years around a decade ago, and revisiting it, it’s still as jarring and wild as ever.

SASAMI’s The Seed has such an interesting pared-down rhythmic energy.

Idiot Box feels especially resonant for me, a famous waster of time (though in my case it’s more an idiot rectangle).

Brothers in Arms has lived in the back of my mind since I encountered it years ago in what might be the greatest needle-drop in television history, on The West Wing’s greatest episode, Two Cathedrals.

The entre score for The Thin Red Line is excellent, but the tracks which feature the choral hymnody of the Choir of All Saints from Honiara in the Solomon Islands make my hair stand up.

Speak Up!

My name is Andrew Bell; I live in Anchorage, and while I don’t want to drag other folks into this, you’re welcome to look up where I work. My personal opinion is that Donald Trump is an awful President and an evil man. Here’s why I think it’s more important than ever to say all that:

We’re in the immediate discourse wake of the tragic assassination of Charlie Kirk, which was itself a violent assault on the free speech rights of all Americans, regardless of opinion. In the online cacophony, there are a whole myriad of people covering themselves in various shades of ignominy by saying things they shouldn’t say, ranging from the very stupid to the actually malevolent. There are also a lot of people reacting in exactly the way you’d expect a normal, decent, human being to react to events in the news, but obviously that doesn’t stick in the brain or catch the algorithm in quite the same way. There are folks on the right citing specific grievances or statements people on the left have done or said which in many cases really aren’t defensible at all, and some folks are understandably upset about what feels like a threat to them – as I often have been by things some folks on the right have said to people like me. I’ve got no quarrel with those folks.

I do have a quarrel with the people who are seizing upon this moment as an opportunity to try to use the political power their side currently holds to get revenge on folks they disagree with because of their resentments, simply on the basis of that disagreement. Kirk’s murderer is in custody and will rightly be prosecuted for this terrible crime against human life, which also was an attack on freedom of speech in practice. That’s a given. What’s not a given is whether or not there will be any consequences, not for the people calling for vengeance, but for the officeholders actually abusing their power to violate the Constitution and suppress speech they dislike – first and foremost, the President.

You may be wondering why I didn’t begin by criticizing Kirk, since that’s what people are supposedly getting in trouble for. I’ve already said what I had to say about our disagreement; the poor fellow is dead and his family is grieving, and I don’t think there’s any real reason for me to say more. I’m criticizing the President, however, because we all know that this attempt to punish critical speech isn’t about Charlie Kirk at all—his death is simply being used as an occasion by Trump to do what he always wanted to do anyway, and punish the only political speech he actually cares about stopping – anything that touches his own ego. The President has made a number of comments which make this motive undeniably clear.

The other person this isn’t about is Jimmy Kimmel, who has momentarily become the face of Trump’s repression of speech, just as Kirk briefly became the face of the victims of political violence in America. Frankly, I can’t believe I’m having to say anything defensive of Kimmel at all, who, if we ignore Trump for moment, is an infamously dull late-night host, who knowingly or unknowingly made a claim about the assassin’s politics that was baseless, false, and stupid, and got fired either for that, or because that provided a good opportunity for the network to prune their expenses (that depends on their internals which I don’t know). But we can’t actually ignore Trump, who has been very clear today as in the past about his desire to suppress the business operations or pull the FCC licenses of networks that criticize him, nor can we ignore his FCC commissioner, who appears to have pressured ABC-Disney into pulling Kimmel’s show, nor can we ignore the context that precedes their explicit remarks—the obvious fact that the network has reason to expect business consequences for criticizing or embarrassing Trump or his allies, or even for failing to flatter him. If Kimmel were fired as a media personality because he said something offensive, that’s one thing; but if he was fired because of implicit pressure of retribution using the power of the executive branch, then that is a complete inversion of the First Amendment.

So for that reason, Trump cannot be allowed to get away with this. He’s tremendously unpopular, but he and his most rabid fans want to use the power they currently hold in government to try to punish or intimidate people who speak up against them, and the easiest way for them to do that is by trying to throw around the weight of the federal government in a way that imposes costs on employers who don’t fire outspoken staff. Obviously there are cases where someone says something so offensive and unprofessional in public that it impacts their ability to do their job; but criticizing, even harshly, or making jokes at the expense of the President or his allies doesn’t rise anywhere close to that level—in fact, it’s perhaps the most typical sort of American political speech. But Trump may succeed at suppressing this simple sharing of political opinion in the public square in practice—the freedom, in some sense the primary freedom our ancestors fought for in the Revolution—if a few people speak out, the least sympathetic ones lose their jobs, and, seeing this, everyone else decides to just bite their tongue in prudence. The one way to fight that is to speak up now, and insist on what we all grew up being taught – that this is in fact a country with freedom of speech, and that it is safe to exercise that freedom in the faith that our fellow Americans will not let us down.

Here are some sources:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/17/business/media/abc-jimmy-kimmel.html

And even my favorite film critic is having to write about politics now: https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2025/09/jimmy-kimmel-live-suspension-late-night/684250/

The Bard of the Yukon

Robert Service gained fame as the ‘Bard of the Yukon,’ and before I was really aware of him as a specific writer whose name I remembered, I was very familiar from childhood with his ballads depicting the Klondike gold rush in amusing verse. Moving to Alaska seemed the proper occasion to finally read his collected poems, which I recently finished, but while his Yukon ballads are certainly his best work, perhaps his most resonant writings for me are his painfully self-aware musings on his mediocrity while living in Paris. It’s hard to know how to feel about relating to them, because on the one hand it’s encouraging that a tremendously successful poet whose work is being read a century on struggled with the sense that his work was not as good as he might have liked; but on the other, perhaps it’s discouraging that, instead of finding this as evidence to refute self-doubt, I actually tend to agree with the substance of Service’s self-criticism, in the sense that his work is more populist and at times plodding, rather than reaching the heights of poetry others achieved. To be clear, Service was a very good poet and a great expositor of both the air of the gold rush and the vagaries of poetic life in war-torn Europe. I certainly can’t write like he can. I just find the grain of truth in his self-critique discomfiting; he doesn’t seem to, to his credit, having openly accepted his limitations. I suppose this is a kind of mature humility that is probably more important than producing great art.

I’ve quoted or excerpted highlights from his work below, starting with his most famous, and greatest poem, which screams out the truth that life alone is not enough—we are filled with longing akin to madness. This is truly an enduringly great work of art, and it is absolutely true to what the country is like.

The Spell of the Yukon

“I wanted the gold, and I sought it;

I scrabbled and mucked like a slave.

Was it famine or scurvy—I fought it;

I hurled my youth into a grave.

I wanted the gold, and I got it—

Came out with a fortune last fall,—

Yet somehow life’s not what I thought it,

And somehow the gold isn’t all.

No! There’s the land. (Have you seen it?)

It’s the cussedest land that I know,

From the big, dizzy mountains that screen it

To the deep, deathlike valleys below.

Some say God was tired when He made it;

Some say it’s a fine land to shun;

Maybe; but there’s some as would trade it

For no land on earth—and I’m one.

You come to get rich (damned good reason);

You feel like an exile at first;

You hate it like hell for a season,

And then you are worse than the worst.

It grips you like some kinds of sinning;

It twists you from foe to a friend;

It seems it’s been since the beginning;

It seems it will be to the end.

I’ve stood in some mighty-mouthed hollow

That’s plumb-full of hush to the brim;

I’ve watched the big, husky sun wallow

In crimson and gold, and grow dim,

Till the moon set the pearly peaks gleaming,

And the stars tumbled out, neck and crop;

And I’ve thought that I surely was dreaming,

With the peace o’ the world piled on top.

The summer—no sweeter was ever;

The sunshiny woods all athrill;

The grayling aleap in the river,

The bighorn asleep on the hill.

The strong life that never knows harness;

The wilds where the caribou call;

The freshness, the freedom, the farness—

O God! how I’m stuck on it all.

The winter! the brightness that blinds you,

The white land locked tight as a drum,

The cold fear that follows and finds you,

The silence that bludgeons you dumb.

The snows that are older than history,

The woods where the weird shadows slant;

The stillness, the moonlight, the mystery,

I’ve bade ’em good-by—but I can’t.

There’s a land where the mountains are nameless,

And the rivers all run God knows where;

There are lives that are erring and aimless,

And deaths that just hang by a hair;

There are hardships that nobody reckons;

There are valleys unpeopled and still;

There’s a land—oh, it beckons and beckons,

And I want to go back—and I will.

They’re making my money diminish;

I’m sick of the taste of champagne.

Thank God! when I’m skinned to a finish

I’ll pike to the Yukon again.

I’ll fight—and you bet it’s no sham-fight;

It’s hell!—but I’ve been there before;

And it’s better than this by a damsite—

So me for the Yukon once more.

There’s gold, and it’s haunting and haunting;

It’s luring me on as of old;

Yet it isn’t the gold that I’m wanting

So much as just finding the gold.

It’s the great, big, broad land ’way up yonder,

It’s the forests where silence has lease;

It’s the beauty that thrills me with wonder,

It’s the stillness that fills me with peace.”

Other excerpts I wanted to share:

From A Rolling Stone:

“To scorn all strife, and to view all life

With the curious eyes of a child;

From the plangent sea to the prairie,

From the slum to the heart of the Wild.

From the red-rimmed star to the speck of sand,

From the vast to the greatly small;

For I know that the whole for good is planned,

And I want to see it all.”

Just Think!

“Just think! some night the stars will gleam

Upon a cold, grey stone,

And trace a name with silver beam,

And lo! ’twill be your own.

That night is speeding on to greet

Your epitaphic rhyme.

Your life is but a little beat

Within the heart of Time.

A little gain, a little pain,

A laugh, lest you may moan;

A little blame, a little fame,

A star-gleam on a stone.”

Pilgrims

“For oh, when the war will be over

We'll go and we'll look for our dead;

We'll go when the bee's on the clover,

And the plume of the poppy is red:

We'll go when the year's at its gayest,

When meadows are laughing with flow'rs;

And there where the crosses are greyest,

We'll seek for the cross that is ours.

For they cry to us: Friends, we are lonely,

A-weary the night and the day;

But come in the blossom-time only,

Come when our graves will be gay:

When daffodils all are a-blowing,

And larks are a-thrilling the skies,

Oh, come with the hearts of you glowing,

And the joy of the Spring in your eyes.

But never, oh, never come sighing,

For ours was the Splendid Release;

And oh, but 'twas joy in the dying

To know we were winning you Peace!

So come when the valleys are sheening,

And fledged with the promise of grain;

And here where our graves will be greening,

Just smile and be happy again.

And so, when the war will be over,

We'll seek for the Wonderful One;

And maiden will look for her lover,

And mother will look for her son;

And there will be end to our grieving,

And gladness will gleam over loss,

As — glory beyond all believing!

We point . . . to a name on a cross.”

Faith

“Since all that is was ever bound to be;

Since grim, eternal laws our Being bind;

And both the riddle and the answer find,

And both the carnage and the calm decree;

Since plain within the Book of Destiny

Is written all the journey of mankind

Inexorably to the end; since blind

And mortal puppets playing parts are we:

Then let's have faith; good cometh out of ill;

The power that shaped the strife shall end the strife;

Then let's bow down before the Unknown Will;

Fight on, believing all is well with life;

Seeing within the worst of War's red rage

The gleam, the glory of the Golden Age.”

From L’Envoi:

“Oh spacious days of glory and of grieving!

Oh sounding hours of lustre and of loss!

Let us be glad we lived you, still believing

The God who gave the cannon gave the Cross.

Let us be sure amid these seething passions,

The lusts of blood and hate our souls abhor:

The Power that Order out of Chaos fashions

Smites fiercest in the wrath-red forge of War….

Have faith! Fight on! Amid the battle-hell

Love triumphs, Freedom beacons, all is well.”

My Masterpiece

“It’s slim and trim and bound in blue;

Its leaves are crisp and edged with gold;

Its words are simple, stalwart too;

Its thoughts are tender, wise and bold.

Its pages scintillate with wit;

Its pathos clutches at my throat:

Oh, how I love each line of it!

That Little Book I Never Wrote.

In dreams I see it praised and prized

By all, from plowman unto peer;

It’s pencil-marked and memorized

It’s loaned (and not returned, I fear);

It’s worn and torn and travel-tossed,

And even dusky natives quote

That classic that the world has lost,

The Little Book I Never Wrote.

Poor ghost! For homes you’ve failed to cheer,

For grieving hearts uncomforted,

Don’t haunt me now…. Alas! I fear

The fire of Inspiration’s dead.

A humdrum way I go to-night,

From all I hoped and dreamed remote:

Too late… a better man must write

The Little Book I Never Wrote.”

I take some humorous encouragement from his poet-friend MacBean’s overly pessimistic prophecy in hindsight (though perhaps I should not, for the manner in which is failed to come true owes much to the war which was about to break out the month after he said it, in July 1914): “We are living in an age of mediocrity. There is no writer of to-day who will be read twenty years after he is dead. That’s a truth that must come home to the best of them.” And in the same entry, Service adopts a very different mindset in regarding his own work: “And as it draws near to its end the thought of my book grows more and more dear to me. How I will get it published I know not; but I will. Then even if it doesn't sell, even if nobody reads it, I will be content. Out of this brief, perishable Me I will have made something concrete…”

While walking cross-country in Finistere, Service reflects on an ailment familiar to many of us: “My dreams stretch into the future. I see myself a singer of simple songs, a laureate of the under-dog. I will write books, a score of them. I will voyage far and wide. I will… But there! Dreams are dangerous. They waste the time one should spend in making them come true. Yet when we do make them come true, we find the vision sweeter than the reality. How much of our happiness do we owe to dreams?”

“Calvert, my friend, is a lover as well as a painter of nature. He rises with the dawn to see the morning mist kindle to coral and the sun’s edge clear the hill-crest. As he munches his coarse bread and sips his white wine, what dreams are his beneath the magic changes of the sky! He will paint the same scene under a dozen conditions of light. He has looked so long for Beauty that he has come to see it everywhere….Calvert tries to paint more than the thing he sees; he tries to paint behind it, to express its spirit. He believes that Beauty is God made manifest, and that when we discover Him in Nature we discover Him in ourselves. But Calvert did not always see thus. At one time he was a Pagan, content to paint the outward aspect of things. It was after his little child died he gained in vision. Maybe the thought that the dead are lost to us was too unbearable. He had to believe in a coming together again.”

From L’Envoi:

“And so, frail creatures of a day,

Let’s have a good time while we may,

And do the very best we can

To give one to our fellow man;

Knowing that all will end with Death,

Let’s joy with every moment’s breath;

And lift our heads like blossoms blithe

To meet at last the Swinging Scythe.”

A Letter to the Church

Growing up, I was grateful to be in a church that by and large avoided prioritizing politics. The church is first and foremost the visible union of those in Christ, imperfectly signifying the ultimate union of, I sincerely hope, all people in Christ in eternity. Given this, I think it is important for churches to avoid becoming subsumed in the sturm und drang of political debate, because they need to minister to all souls and model a community in which even enemies are neighbors, and no neighbors are shunned.

We must love our neighbors in the reality in which they live, however, and throughout history lives are impacted in many ways by events, including those subject to political controversy. When a natural disaster falls on those around us, we should not ask their political views before helping them. In the same manner, when something akin to a natural disaster in its effect falls on our neighbors, we should not avoid helping them out of a desire to remain politically neutral.

We are presently living through a moment where those who carefully consider both history and the events of the day, from across the political spectrum of mainstream American politics that we grew up with (if you grew up at any point in the seventy years after 1945), recognize as just such a calamity. I do not want the church to endorse political candidates, or commentate on elections; but I think in a moment when institutions are collapsing into a nascent authoritarian lawlessness, and innocent human beings are being wrongfully imprisoned, abused, and discriminated against, we lose the right to act as if everything is normal. We have to either react like humans capable of love and with the capacity to perceive even a scintilla of the truth, or we completely lose our witness.

I realize many people who used to exist comfortably on one side of the political aisle have reacted to circumstance and shifted into a position of independence and great discomfort with both sides, which is a credit to them – this type of shift is difficult and challenging on a personal level. There is, however, a temptation that comes with it – the temptation to find a new way to rise above controversy by answering any wrongdoing by one side with a compensating example of wrongdoing by the other. This was perhaps once a wise and reasonable impulse, but in extreme circumstances it risks reifying a false equivalency. I fear we are too prone to this posture in the church, and that this does real, material harm to people we should protect, because a commitment to defining the middle as equidistant between the two poles cedes control of what is within the ambit of acceptable politics to whoever is willing to run the furthest from that center in their direction, and thus drags the center with them. Some things must remain beyond the pale for those who love justice and mercy.

I think in our case, we have a particular duty to avoid lending our silence as assent to what is currently transpiring around us. We have all seen the statistics on political opinions among Evangelicals, especially Southern Baptists; the head of our flagship institution of theological education and study uses the position the denomination has placed him in to actively, consistently, endorse and support an administration that is doing more violence to the freedoms Americans ask their soldiers to defend, and to the spirit of charity that Christians are called to live out, than any external enemy ever could. In short, to the reasonable member of the general public, we appear by our own association, complicit. Complicit in what? In kidnapping, torture, and murder by neglect. If we want to preserve our witness, and if in fact we want to obey Christ by loving our neighbors, we must not be silent when evil is transpiring in plain view, we must not act as if everything is normal, and go about our business as if all disagreements are simply that – disagreements, without responsibility. To quote Bonhoeffer, “We must finally stop appealing to theology to justify our reserved silence about what the state is doing — for that is nothing but fear. ‘Open your mouth for the one who is voiceless’ — for who in the church today still remembers that that is the least of the Bible’s demands in times such as these?”

But most importantly, we must act in love. I have no interest in the kind of political posturing so many churches do, without actually helping people or risking anything. I believe there is an absolute moral imperative to help those in peril.

When I was a child, I recall a young man from Sudan came to stay with a family in our church. He had walked out of a war, out of a famine, and out of his country to get to safety. He had no legal place to go. The church helped this man, and gave him a future – or rather, the church was merely the instrument passing along the blessing that was not originally theirs to give. Today, there are people like that young man all around us, even in our nearest communities – people with no good options, with nowhere to go – and some of these people are being scooped up by a machinery of evil that is operating not only in our name, claiming to act on our behalf, but also in the name of our God – they are being scooped up, and some of them are being dumped into places like that my refugee friend walked out of – in some cases, the exact same war zone, in fact.

If we are serious about ministering to the needs of our most vulnerable neighbors, we cannot simply stay within our comfortable walls and watch. And, as recent events have demonstrated that no one can have an expectation of safety in any place, if we take seriously the safety of those attending our church, as I know we do, we cannot simply hope or assume that nothing bad will ever happen to our community.