Movies I Saw in 2022

Ok, I’m laughing at myself as I start this one. I’m not sure how many times I can make the joke about me posting something late, but in this case I almost have to. I meant to write this blog at the end of 2022; it is almost Halloween of 2023. Oh well lol.

I want to be very clear, this is not a list of films released in 2022 – I’m going to get to that in another post. I’ve also mostly excluded films released in 2021, because then it would be too heavily dominated by recency bias, especially since 2021 was a banner year for movies. The only thing these movies have in common is that I happened to watch them, some for the first time, some not, during 2022. I’m only going to run through a few titles here that I wanted to mention for one reason or another. In total, I watched 216 movies in 2022.

My Neighbor Totoro

I started the year off right; on January 1, I watched Hayao Miyazaki’s beloved classic, My Neighbor Totoro (1988). This is part of a subgenre of movies that depict rural Japan and which therefore crystallize a very specific sort of nostalgia for the brief time I spent toodling around the chequerboard fields of Funakura. Totoro is a sort of bright mirror, however, because my nostalgia is melancholic, recognizing my own peculiar adult faults and remembering a time where I was both very relaxed and happy, but also often lonely and sad. The film, on the other hand, depicts childhood joy in a way that seems innocent and free. Even so, it’s a film about children facing, in some small way, the anxiety of loss, which is why it has far greater staying power than a lot of other films aimed at children. It’s hard to see a way back to this sort of childhood joy, but I think it’s necessary to believe it’s possible – perhaps to return, to come, as Christ said, as a little child.

Other notes:

· Joe Hisaishi’s scores are always iconic, but this one is particularly magnificent, as anyone remotely familiar with it knows.

· The world is strange and twisted in a sort of unsettling-comforting unity. Cf. Catbus.

· This is the cinematic equivalent of “All shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

Germany, Year Zero

Only a week into the new year, I watched Roberto Rossellini’s stark film, Germany, Year Zero. Released in 1948, only three years after the fall of Berlin, the film takes place in the broken rubble of the desiccated city, and follows a child as he attempts, somehow, to live in a world of shards and ash. Personally, this film challenged the limits of how I think about the world, not because anything in it was surprising (I’ve read plenty about the period), but because I had to confront the fact that there didn’t seem to be a way to act correctly in such a situation. I tend to obsess over what people should do in any situation, how things should be – and Berlin after the fall laughs and spits in the face of such thoughts.

· This is a case of melodrama being fully justified by the actual state of things.

· This is a real case of that standard of fiction, the work that tries to picture what would happen to survivors of the apocalypse. We just usually like to look away from times when that actually happened.

· Part of the tragedy is the image of children with no hope, made even more poignant because, in the light of history, we know that there would eventually be cause for hope, and other things to live for. But I know how hard it is to see that in your own life, even in cases where you intellectually know it to be true.

The Worst Person in the World

I said I wouldn’t write about any films released in 2022 or 2021, but made that rule intending to break it for two movies, just to make a point about their greatness. The first is Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World. This is a strikingly beautiful movie (Oslo is filmed suffused in faded natural magentas and lavenders), and Renate Reinsve gives an astonishing, gentle performance. But more than anything, the film directly addresses my anxiety about wasting my life, and being a small, selfish person. And it reaches a profound and inexplicable state of catharsis, without fantastically compromising the reality of life depicted. If you read a synopsis of the plot, it wouldn’t sound like anything special, but that’s simply a testament to the importance of execution and direction. As it stands, this is one of my favorite movies.

To be completely honest, I don’t know how to relate to catharsis in art. I think that we desperately need it, or at least I do, personally – but my fear is that I arrive at a purely emotional sense of relief, and believe that all will be well, without that necessarily involving spiritual reconciliation. That seems sort of cold to say, and I’m not happy with that doubt; but I think this struggle of whether or not to doubt the cathartic impulse of the moment is, for me, of a piece with the struggle over limited or universal reconciliation and redemption, and that’s not something I’ve really resolved within myself. So when I encounter art that strikes the chord in my soul that echoes Little Gidding’s refrain that “all shall be well, and/all manner of thing shall be well,” I worry that I’m rushing to just accept a Gospel with no demands. But it is, on the other hand, a free gift. And Tolkien wrote about the sudden unlooked for turning, the surprising moment of positive resolution, and I think this feeling is in that tradition.

If that seems like a rambling and personal tangent, perhaps it is – but it’s the thing that most nearly intersects with my own life, and in that way it’s the thing that I have got to say. There’s a mirrorlike quality to the film, at least for me. In the scene were our heroine tears up, looking into the dawn, I felt the shock of reminiscence – I too have climbed the rocky hill in order to be able to weep joyfully into the dawn.

Phantom Thread

Another softspoken movie I saw, perhaps one of the most softspoken, was Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2017 film Phantom Thread, which I will not attempt to define in terms of genre or plot. It’s both very simple and extremely strange, and I think it’s a career high performance from Daniel Day-Lewis, which is matched by Vicky Krieps – a true battle of megawatt performances, conducted almost in whispers. This is the best PTA movie I’ve seen, a film with rich visual textures, a specific quality of light, the calm essential vitality of being. Everything is exactly right.

A Story of Floating Weeds/Floating Weeds

I’m cheating a little with the next, because I watched Yasujiro Ozu’s A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) in February of 2022, and then watched his 1959 remake of his own movie, Floating Weeds, in February of this year. The two have the same plot, and they are both superb. Ozu seems to have cracked the code, realizing that the best way to prevent someone from making a mediocre remake of your movie is to just make a great one yourself first. While the remake is more dynamic in some respects, and has the benefit of glorious Agfa red, a color God decorates heaven with, I actually felt more emotionally moved by the earlier film, especially by Emiko Yagumo’s tremendous mouth acting.

The Passion of Joan of Arc

Another extremely emotional black and white film I saw in February was the 1928 silent masterpiece of Carl Theodor Dreyer, The Passion of Joan of Arc. The film depicts Joan during her trial and, if you’re so inclined, martyrdom, and features the most and probably the best eye acting I have ever seen, from Maria Falconetti. The film is a fragile yet unvanquished image of defiance in the face of sneering, mocking evil, yet without the sort of romanticized erasure of human frailty and fear. I’ve always been scared by stories of martyrs, because I just don’t think I could endure such a trial. And yet, in this film, Joan remains human while becoming a saint.

Lady Snowblood

On a completely different note, Toshiya Fujita’s 1973 revenge classic, Lady Snowblood, is a luridly vivid splash of crimson blood that just rocks. But there’s a tremendous amount of artistry present in the design and direction – there are incredible shots of stunningly white snowy foregrounds within an inky void of black negative space – and into that, the reddest blood imaginable.

Millennium Actress

Satoshi Kon is one of the most beloved directors of animation, who passed sadly long before his time, after directing only four features. In March of last year, I watched all four in a row, and of those four, Millennium Actress is my favorite. The film is a nostalgic collage, blending memories from the life of the eponymous actress with fictive temporalities plucked from her movies. It’s a meditation on the way in which we construct our own nostalgic pasts, whether for gratitude or regret (to the extent that, in nostalgia, they even differ), and paste our memories and created stories together like newspaper cuttings. The imagined relationship that could-have-been becomes a sort of parasocial love affair with one’s own remembrances. The film creates the feeling of age, the sense of astonishment that a life can span so much time, so many different worlds; but it doesn’t only look backwards. Somehow, despite its fascination with nostalgic longing, with might-have-beens, the movie is robustly hopeful in ultimate outlook, and is all the more successful at cheering me up because it feels honest in its treatment of life.

Drive My Car

I said I would break my rule against 2021 releases for two movies, and the second is one which I have watched at least three times since its release, and which has now got the better end of the tie with Worst Person in the World for my favorite film of 2021: Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s monumental Drive My Car. There’s a lot of things to say about this movie. First, the titular car is one of the best-looking vehicles I’ve ever seen in film: a red Saab 900 Turbo. They don’t drive it fast (it’s Japan), but they drive it oh so well.

Second, this has the same thing going for it as Worst Person in the World, to the extent that I view them as somehow twinned. This is a movie about catharsis, about accepting that despite life not being what you hoped for or expected, and despite the wounds we wear, you will be ok. In some respects, this film is even more directly about that than the other, and so of course I can’t even really fully feel that sense of catharsis, without simultaneously feeling doubt – because the way I apprehend catharsis feels like a cheat, like smuggling in the attitude of implicit universalism, or a release from moral risk and responsibility. But I hope that one day, I shall be whole, not perfect, but able, at least, to feel that catharsis and peace when watching a movie like this, and not second-guessing.

Finally, the film has an incredibly cast, all of whom give fascinating performances. I think a lot of people have noted Reika Kirishima as a showstealer, and she is a strange, cryptic presence. The two leads, Hidetoshi Nishijima and Toko Miura, give performances that are all the more emotionally potent for their restraint, for what they do not say. I went into this knowing Miura as a musical artist, and I was surprised and fascinated by her character and presence. But the person who actually stole the show for me was Park Yu-rim. She delivers the culminating monologue of the film, a speech from Chekhov’s play Uncle Vanya, in Korean Sign Language, and in that scene, in near complete silence, the film fully articulates its message – that, acknowledging our pain, we still must live our lives in quiet hope. It’s maybe the best performance and definitely the best scene of the year, and I can’t stop repeating it, because I desperately need the seed of hope amidst reality that it contains.

Last and First Men

I also watched one of the best movies I’ve fallen asleep during (in fairness, I was very tired): Last and First Men. I first became interested in this because I stumbled across the music, composed by its director, composer Johann Johannsson. Sadly, this film was the culmination of his career, as he passed at a young age, so this is also his last and first film. I was so intrigued by the trailer that I read the book as well, a narrative of an imagined distant future, spanning eons of time, written a century ago by Olaf Stapleton. The film boils this story down to a spare monologue of narration by Tilda Swinton (of course). This plays over a series of still black and white shots of decaying concrete Communist monuments. And there are frequent pauses of a minute or more, in which the camera does not shift and the narrator does not speak.

In short, it’s improbable and surprising that this movie works – but somehow, it does. The central arc of Stapleton’s book is a civilization trying to cast about for any source of hope or meaning in a cold, bleak universe, where entropy will eventually run the clock out on history. Johannsson managed to find the perfect way to represent the epitaph of hopeless time in the monuments of a failed regime that gestured toward a better future. It’s haunting and beautiful, even if it does put you to sleep. Having said that, I’m glad I don’t believe in a universe in which the cold heat death of material processes is the final word on life.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

Peter Weir directed the second-best movie of the 1970s, an esoteric, meditative play of soft light and sleepy, otherworldly vibes. But that’s not what I’m here to talk about, because in 2003 he also directed what must be the greatest tall ship movie of all time, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. I have extremely complicated emotions about the British Empire (a villainous enterprise of exploitation that created the world in which a disproportionate of the culture I grew up with and have nostalgia for was created), and by extension, the Royal Navy, but my emotions about this movie are extremely simple: it’s great! Part of it is that I love movies that show professionals at work, executing processes with aplomb; part of it is probably that the RN is the prototype of my beloved Starfleet, the example par excellence of that sort of professionalism (it helps that Crowe has a Shatneresque energy to him). I think ultimately, there’s nothing as romantic as a tall ship on a wide open sea.

Boyfriends and Girlfriends/Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle

In short succession I watched two of Eric Rohmer’s little films (I use the term affectionately, not pejoratively), Boyfriends and Girlfriends, and Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle. I feel like these quiet pieces, in which little seems to happen except for ordinary life, with warm colors and a gentle spirit, are mining the same vein as Ozu’s later work. I also have a very strange nostalgic fascination with western Europe in the 1980s, possibly based on architectural books I read as a child, and these films fit nicely into that grain.

The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun

In May I watched The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun, a film by the great Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty, and this short movie feels like some sort of perfectly cut topaz or amber gem. The whole is encapsulated in the part, in one sequence when the characters go dancing down the street in a way I can’t really even describe – but it’s electrifying.

Atonement

I also watched Joe Wright’s 2007 film, Atonement, which I had been meaning to get around to for a long time. For me, it’s a fascinating collision of nostalgia and antinostalgia; longing for worlds which never got to exist, and, at the same time, rebuking that with harsh reality, nostalgia collapsing into guilty regret, and all played out against the backdrop of a wartime England that is, for many like me, a site of great nostalgia, but which was also at the epicentre of the ultimate collapse into imperial guilt and regret. It’s also a gorgeous film, which includes one of the most successfully elegiac sequences I’ve ever seen.

Dodes’ka-den

Everyone loves Akira Kurosawa, and I’m no exception. Working my way through his filmography, I came upon Dodes’ka-den, and was shocked that the great director had made something simultaneously so artistically compelling and successful, and so – well – ugly. I thought I knew what sort of films Kurosawa made, and was very comfortable with them, but this was jarring and nauseating. It’s never going to be one of my favorite of his films, given my sentimentalist, cathartic biases, but I’m going to remember it with great respect for the truth it depicts.

The Virgin Suicides

The Virgin Suicides is as good an argument for nepotism as you can make. Personally, I think it’s probably Sofia Coppola’s best work. It manages to crystallize an incredibly specific sort of narrow hopelessness one gets in adolescence, when you can’t actually see a path into the future. To the extent that this is the condition of mortal life, it’s a universal text, even though all is portrayed through an extremely particular suburban moment.

Juno

When I watched Juno, I had no expectation that I would be so thoroughly won over by it, but the film is so winsome and charming that I had to watch it a second time in short succession. It’s the perfect combination of wit and sincerity. And for all that this is a dialogue-driven film, the most powerful line in the movie is read, not spoken. What an optimistic little movie!

Silence

I think the greatest and most profound movie I saw in 2022 was Silence, a movie that so transfixed me that I not only immediately read the novel it was adapted from, but also read someone’s dissertation on the hidden Christians of the southwestern islands of Japan. In my view, this is Scorsese’s best film, but that’s not the most surprising thing I could say – this movie was designed for me in a lab. It combines calling out to God, trying to hear Him respond, with deep practical theological angst, and all of that through a beautifully reconstructed early Edo-period rural Japan. I don’t have the same sort of complex the protagonist does, but I remember in childhood being anxious about the idea of tests of faith in martyrdom. I’m not even sure what I think about what the film seems to be suggesting about pride and martyrdom, or mercy – I think I may actually not agree, if I’m understanding it correctly – my view of the potential value of martyrdom is perhaps not deconstructed much at all. But I love the incredible sense of empathy the film has, and as a weak person, it seems to be begging for room for those of us who are weaker. And, without spoiling anything, I will say that I have often been sitting and thinking, and the final shot of the film will come unbidden to mind, and I will begin to cry.

Andrew Garfield should have won Best Actor for this, and someone in the staggeringly good cast of supporting actors should have also walked with an award – take your pick as to who.

Paris, Texas

Paris, Texas honestly wasn’t doing that much for me for most of its runtime. I could tell it was well-crafted and looked nice, but it just wasn’t connecting – until the end. The last conversation through glass really broke through to me, and I was left reflecting on a story about what love is after you feel you’ve lost your right to it, yet still find it extended nevertheless. It’s a picture about grace.

Days of Being Wild

Days of Being Wild, another Wong Kar-Wai movie in which the director wonders what would happen if everything was teal, is a film where you can actually feel and smell the humidity as you watch it. And it captures the dread anxiety of knowing that you’ll hate yourself if you do something that you’re nonetheless drawn to, even as you feel anxious that you don’t want to hate yourself. Possibly his best film I’ve seen? I really will have to think about it.

Whisper of the Heart

Whisper of the Heart was made by Yoshifumi Kondo, the man trained to be the successor to Miyazaki and Takahata at the head of Studio Ghibli, but he tragically died after only directing this one feature. Miyazaki has made 12 movies; Takahata made about 7, I think. Yoshifumi Kondo only ever got to make one. His movie is as good as the best movie from each of the others; it’s on par with the best thing any anime director has done.

You might not believe this, but it's true: near the beginning of this film I paused because I was sad and discouraged, by two specific feelings, not because of this film but occasioned by its hopeful sentiment. First, that my life would never make sense like a story does, and second, that it has declined, and I no longer enjoy things as I did, or am as good as I was. Then, almost halfway through the movie, our heroine voiced exactly those same feelings. Now, maybe I have more cause to be anxious about life not making sense, since I'm much older, but still, it's something. This is a deeply hopeful precious gem.

A Hidden Life

I watched Malick’s A Hidden Life alone in a room in the Catholic center for dialogue and prayer a block away from Auschwitz. It seemed the right place for it. Once again I feel that Malick has perhaps the best grasp on the Beautiful and Good of anyone working; he also has the strangest way of editing conversations I’ve ever seen.

Talking about our comfortable idea of Christ, as opposed to the Man of Sorrows, and thinking about how we live, and try to avoid suffering, is really challenging for me, and speaks into a lot of my anxiety about what I should or shouldn't do, but don't. I struggle with heroic narratives because they suggest a higher moral possibility than I want to have to contend with. I just have a lot of anxiety about the consequence of the divide between people who will die for the truth, and those making excuses not to, since I feel like someone who makes excuses to do the easy thing.

Moulin Rouge!

I realize that Moulin Rouge! elevates adolescent feelings and crushes to the level of something noble and true in a way that doesn’t fully pass scrutiny, but it’s just done so compellingly and with such unembarrassed sincerity that it always wins me over. It’s both a sentimental picture of romantic, emotional love defeating cynicism, and a deeply comic film in which a coquettish Jim Broadbent grunts out Madonna lyrics (he should have gotten an Oscar for this).

First Reformed

On First Reformed, a film I took very seriously but was deeply puzzled by: I have never quite known how to process really serious arguments about the warnings on climate change, because it's such a challenge to my own desire for optimism and my rootedness in the idea of the status quo, the idea that some things get worse and some things get better, and it all evens out and we muddle through like we always have. I know that there is a religious and eschatological answer to all of this, which I believe in, but it's difficult to foreground that because of my own anxieties about eternity, and because of my reaction against the end times obsession among Evangelicals when I was growing up. Maybe all of this is just the recognition that while I believe the climate models and think more needs to be done, I’m less willing to significantly change my lifestyle, and unwilling to ask others to forgo ascension into the middle class, so maybe I'm just unwilling to do triage, so firmly do I have to believe in a possible future that is better than the present, and not worse - and now we're back to eschatology and eternity, and the fact that we're all deluding ourselves the moment we forget Death. But we also must live here, now, and our children. And I will say this: I’m not really an activist, and I don't tend to support radical sacrifices. I don't support denying the developing world power, and I don't support seriously reducing the middle class lifestyle, although I worry about how that interacts with my Christianity, given Christ's call to deny ourselves - but I don't want to fall into a kind of Puritan impulse to sacrifice for its own sake, that life has to be hard. And I will also say that I think it is good to bring children into the world, even this world. But this all just sets off my anxiety of conviction - in church they say we have to change, and I feel unwilling, and am anxious, and in the political sphere activists say we need to change, and I feel unwilling, and become anxious. It's tiring, although maybe that's an excuse. I think I've just never really been able to get around my sense of anxiety about certain kinds of disruption, perhaps because there's no clear limit to it, or perhaps just because I don't want life disrupted with no sense of control over it. And I think I've never fully been able to get on board, because while I can be appalled by the destruction of the forests, I always am thinking about civilization and its maintenance, and there's a part of me that worries it doesn't work if too much is changed. It's like when people started singing about removing dams - immediately I thought, "dams are important, though - you can't realistically impound enough irrigation water for droughts without them." But I worry that makes me a bad person. I think that cui bono is the right question, and I think the distinction between me and some folks a little further to my left on this is that some of them would focus that answer on large corporations and the holders of global capital, while I am always worried that actually, it's not just them, it's all of us, too. And I have no idea what to make of the ending.

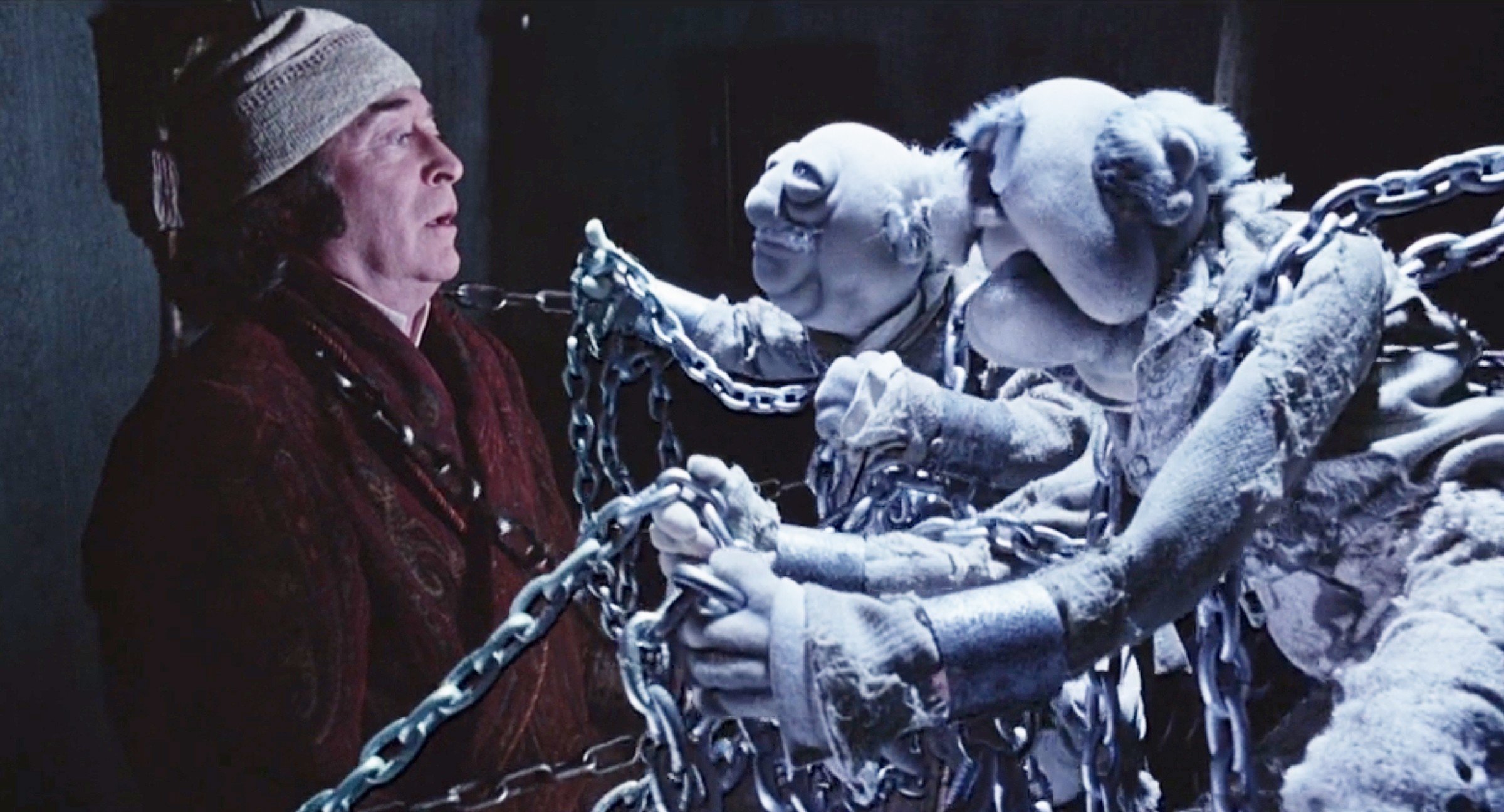

The Muppet Christmas Carol

I ended the year with the greatest Christmas movie of all time, The Muppet Christmas Carol, finally restored to the original version I remembered from my childhood VHS, with the crucial song that was bizarrely cut from the DVD for many years. This movie is somehow one of my favorite films of all time, even though it provokes my fear of hell and the pressure of some sort of works-repentance soteriology. Maybe that sounds like a silly reaction to Statler and Waldorf in ghostly chains, but it’s a real thing I struggle with, so it’s interesting that my affection for this is unimpaired. At any rate, the deeper pattern of the story rings true, and Caine gives an incredible performance. There’s no reason you couldn’t make any story, with every bit of its seriousness and sentiment, with muppets.