Archive

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- January 2023

- September 2022

- August 2022

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

June 2023 in Music

Kevin Penkin’s anime soundtracks have been a revelation – grand orchestrations simultaneously classical and contemporary, and always with some high, haunting crescendo of horns, breaking emotionally – and always with an undercurrent of the eldritch and bizarre.

In June, I got really into Depeche Mode. This is my pattern – there will be some beloved classic artist whose work would always have appealed to me, and yet I will take years and years to get around to them – until I suddenly do. This is exactly the kind of sound I’m ‘nostalgic’ for – a kind of back-projected, learned nostalgia for a past I didn’t have. In other words, a pose. But as far as this type of new wave/synth pop is concerned, I’m shameless.

The next three songs are also from that same time period, but they’re otherwise quite distinct – contrast Bjork’s squawking cries, all rough edges, with Ultravox’s ultra-smooth sound, as if they’d taken a sander to their music. And of course Peter Gabriel is just my favorite.

After that it’s more oddness Mili, and then more J-Pop, and I’ll just specifically shout out ZOMBIE-CHANG’s terrific vocal style. She manages to sound incredibly droll and utterly done with everything, in a way that adds character to the music.

Then I decided to revisit 2014, when I listened to the radio on my commute and enjoyed WALK THE MOON’s optimism – and you know what, it’s not a bad thing from time to time.

Junkie XL pulled off a gently haunting score for Three Thousand Years of Longing, not really what you’d expect from the Mad Max guy.

Late Yellowcard is still pretty good, despite what some folks might say.

Fly-day Chinatown is perhaps the greatest example of early ‘80s Japanese city pop, and it was probably my song of the summer – indescribably grand.

May 2023 in Music

Of course we begin May, the crowning glory of spring, with Takagi, who is always gentle and warm. I think a lot about gentleness; I feel that we encounter God in the gentle beauty of small things, like dew on a flower or the pre-dawn chatter of birds. But saying that comes with its own doubtful anxiety, because in seeing God as gentle and near, immanent in the beauty of creation, I tend to also interpret that as a sort of universalistic or unqualified reassurance, which sits in tension with my understanding of theology. For me, this is a sort of veil between myself and fully experiencing the sense of safety and peace betokened by small, beautiful things. But I do think that the nearness, the immanence, and the gentleness of God in creation is indisputable, regardless of my confusion.

Ok, I admit I revisited Born Slippy because my favorite film podcast did an episode on Trainspotting. Otherwise this seems a little incongruous for me. But it does fit with my listening in one sense: it’s some real fin-de-siecle stuff, rattling around the great empty echoing chamber of the end of history.

Clammbon put out a new album this year, and twenty years into their career they haven’t lost their step, and no one sings with quite that specific sort of strange plaintiveness as Ikuko Harada.

I went to see Guardians 3, and there’s a sequence where they play some diegetic music which is meant to be alien, to sound like nothing ever before heard on earth – but being me, I immediately recognized it as Vocaloid Japanese music, and looked it up as soon as I left the theater. Make of that what you will.

I’m Always Chasing Rainbows – this was another from the soundtrack of Guardians, and it’s an example of how I’m very basic in respect to big swelling rock chords. As for Ancient Dreams, Marina just never misses the opportunity to be musically striking. As for Mili, I honestly don’t know how to describe their music – but I like it. I stumbled onto Mallrat in May, and just kept circling her music. And of course, Pacific Coast is just pure highway cybervibes.

Purple Clouds, however, is quite something. Kensuke Ushio weaves a delicate ending to Naoka Yamada’s stunning television adaptation of the Heike Monogatari, and this score plays over the final thesis of a story which concludes that the only response to death and loss is to pray and remember. What else can we do?

April 2023 in Music

As before, I’m just going to highlight songs I have something to say about, not go through every single one. For me, the rewarding thing is actually making the playlist, which serves as a snapshot of what I was listening to at the time.

I love Peter Gabriel, and I found his score for The Last Temptation of Christ haunting and weird, with all the mysticism that term implies. In particular I became fascinated by the track It Is Accomplished, which drops a set of tubular bells down a staircase to announce the final break of tension, the catharsis of the world. Jerry Goldsmith turned in a surprisingly classical, old-Hollywood overture for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (a film I personally had underrated). The lush strings sound like they could belong to a golden age picture. Florence + The Machine’s Between Two Lungs is about building up steam until achieving a sort of runway, breakneck pace – and that’s perfectly typical of her music, and why it works so well.

I’m a La La Land defender, but if the movie suffers from anything it’s that its first two tracks are so much better than anything else in the film. There’s a sort of traveling line of melody in them that is a complete earworm and came to dominate my brain for several weeks. I’ve always found Janelle Monae an undeniably great talent whose work is always catchy, and St. Vincent’s Nowhere Inn is a welcome addition to a subgenre of southwestern-inflected music that is both warm and bleak.

For his film Suzume, Makoto Shinkai wisely brough RADWIMPS back for the score, and they in turn brought in Kazuma Jinnouchi’s eerie cyber-choirs to create the score for an movie all about eldritch locations.

I love The Sundays, and I found that Summertime is upbeat, but it insists on happiness in a sad voice, whereas Cry is melancholic in a contented, almost satisfied way. Finally, Tanukichan’s And More is an all-subsuming flood tide of composite warm noise.

March 2023 in Music

I’m making a concession to reality – something I greatly struggle with. I can’t stand admitting that time is limited, and that I’m simply not going to do everything I planned in the way I planned in the time I planned – but sometimes it’s impossible to maintain the illusion. So, I’m going to post my playlists for each month, but I’m only going to comment on the songs I feel like saying something about, and only briefly – I’m not going to attempt to conjure up whole paragraphs about each, because I simply don’t have that much to say, and because trying to do so has delayed these posts to a ridiculous degree.

Having said that, here’s some of the music I enjoyed in March:

The first thing I noticed, revisiting this several months after making the list, was that between Sum 41 and Reliant K I appear to have been nostalgically revisiting high school, which is not a bad thing to do when it comes to music. When you’re young it can be easier to accept openly emotional music without trying to critique it through the filter of sophisticated taste. Sum 41 in particular reminds me of the time when punk Naruto music videos on primordial youtube were the height of sentimentality.

And let’s be honest, sentiment or aesthetic sensation is, at the end of the day, the whole explanation for the inclusion of any song. Sometimes it cuts through regardless of what a song is actually about. Rocky Mountain High is a beautiful hymn to the beauty of nature, even if I’m deeply opposed to the idea that bringing more people to a place is a bad thing. Can a song be misanthropic and also beautiful? I suppose it can.

Everything CHVRCHES puts out reliably serves to help me cut through the mental fog of a tired Monday morning, Just Like Honey is yet another example of an end-of-century warm fuzzy mass of sound that I like, and Humbert Humbert continue to do variations on the same musical themes and emotions. Personally, their music makes me feel they are gardeners gently tending to a tiny, delicate crocus (I am the crocus). And Saho Terao’s music slipped into my feed and was immediately slotted into my ever-expanding collection of teary Japanese music.

Carter Burwell’s True Grit score is a rousing yet understated accompaniment to what might be the Coens’ finest work. And yes, in 2023 I finally discovered Jamiroquai, thanks to memes. The next couple of tracks showed up on the excellent soundtrack for Licorice Pizza, and sparked a minor obsession where I would play them every morning while I commuted for about a week or two.

After that come three excellent pieces from film scores, another hopeful work from Hitsujibungaku, an admission that yes I do like bagpipes, and a Takagi which reminds me of the time I was a child staying at a motel in Australia, and through the evening humidity and the symphony of cicadas came the flashes of distant lightning, and the approach of a glorious summer storm.

Alaska Summer 2023

I arrived in Alaska in the middle of June. Since then, I’ve been learning my new job, getting to know the good people I work with, and settling into my apartment, neighborhood, and now, church. But I’ve also been cramming as much mileage on my car as possible and taking all the pictures I can. I’m blessed with a short commute, so during the week I don’t drive very far. Instead, I have redistributed all that mileage to the weekend, in an attempt to probe just how far you can reasonably get in a single day. My only wish is that there were more roads to drive down – for being the largest state in the Union, Alaska only has a few highways.

There are, in fact, only two ways to leave Anchorage – you can go south on the Seward Highway, or north on the Glenn (and technically on the Old Glenn, but that’s almost the same thing). So, over the first couple of weekends, I probed south, along a road which hugs the broad tidal flats of Turnagain Arm, which separates Anchorage from the Kenai Peninsula. At the end of the Seward Highway is, well, Seward, the town named after the great Secretary of State who arranged Alaska’s purchase, and who is one of my favorite American politicians. Near Seward is the Exit Glacier, which is itself merely a tiny protuberance of the much larger Harding Icefield. If, instead of going to Seward, you turn onto the Sterling Highway and drive about 140 miles further, you will come to Homer, a town built on and around a spit of land jutting into Kachemak Bay. When I was there, the mountains just across the bay seemed to be emitting a strange cloud of fog or dust which almost seemed to glow.

For the long weekend of the Fourth of July, I turned North. Just northwest of Anchorage, the Matanuska Glacier creeps across the valley floor, bizarrely lower than the highway, a monstrous incongruity of ice. Continuing on, I turned south, slipped through a darkly verdant canyon of hanging glaciers that seemed to exhale clouds and equally white waterfalls, and came to Valdez. If you look at the third picture below, on the right you’ll see the modern port and on the left the terminus of the Trans-Alaska pipeline, from which oil is shipped out through Prince William Sound. It was there, just a few miles out of Valdez, on Good Friday, 1989, that the Exxon Valdez ran aground and spilled its cargo into the sea. And, in the foreground of the photo, you can see some of the land on which the town used to sit, before it was destroyed by subsidence in the 1964 earthquake, the most powerful ever recorded in North America. As a consequence of the earthquake, the entire town was relocated. This earthquake, of course, also took place on Good Friday.

I did a silly thing, leaving Valdez – I treated it as a short detour on my way further east, and tried to reach McCarthy, which sits at the end of 60 miles of dirt road, the extremity of another road. I tried to reach it in the same day in which I had left Anchorage and visited Valdez, and I almost got there (though it would have been very late). Unfortunately, bouncing along the potholes, the seal on my oil pan came loose, and I suddenly discovered there was an indicator light on my car that I’d never seen before. Fortunately I was able to make it back to Glennallen where there is what has to be the busiest gas station in the state. Having thus altered my plans impromptu, I slept in my car for a couple of hours, and when I stepped outside for just a few second, I found myself immediately covered in vicious mosquitoes. They are somehow even worse than described.

As I proceeded north up the Richardson Highway, I discovered the reason why. It turns out that the typical interior landscape of Alaska is a series of enormous ponds and marshes, stretching as far as the eye can see, and incubating untold trillions of mosquito eggs. But just a little further, and it all became worth it, as I crossed the Alaska Range, and saw its brilliantly-colored slopes. And there, in front of them, like something out of a dream, ran the pipeline. I wasn’t surprised to see it, of course, but I still wasn’t quite prepared for how strange it looks, like an alien spacecraft landed on earth. And it just went on and on, without ceasing. It reminded me of the Great Wall receding, ridge after ridge, into the hazy distance.

I stayed in a small cabin in Delta Junction, and I was thrilled to discover myself in the landscape that has so long fascinated my imagination – the endless birch woods of the north. I imagine the Sweden of my ancestors, I try to imagine medieval Russia and the river routes to Byzantium and Baghdad, and I cannot imagine the vastness of Siberia, try as I might. But these woods are a picture of it.

The following day I headed south again, but this time I turned off to the west, to cut over the highlands on the Denali Highway, over a hundred miles of dirt road that mostly runs over land just barely too high to grow trees – which is not as high as you’d think. To the north, under the louring sky, gaps in the wall of mountains opened here and there to disgorge colossal frost-giants. Across my path, rivers unspooled like silver threads on green silk.

After that weekend, I decided to stay closer to Anchorage, so I went up to the Independence Mine, an abandoned mining town which is now a public park. It wore a forbidding aspect, as twisted and broken mine cart rails hung in the fog and rain, and it was difficult to picture as it must have been, filled with people and bustling with life.

I have a fascination with glaciers, and as soon as I became aware of the Exit Glacier trail, I knew that hiking it had to be a top priority. The trail starts almost at sea level, in the birch forests along the river coming from the base of the glacier. From there its stone stairway climbs three thousand feet up, skirting the edge of the Exit Glacier. The summit holds the prize: an unbeatable view into just a portion of the vast Harding Icefield, which extends beyond the horizon. There’s nothing quite like gazing into a vast sea of ice. I even spotted a tiny figure walking across a part of the ice; you can see them in two of the pictures below.

The problem I ran into was not ascending the trail, but descending. I had not done a hike like that in a couple of years, and going down the stone stairs I was beset by terrible leg cramps and fits of shaking. Fortunately I had plenty of daylight to burn, and I was able to use the distended descent time to listen to a fascinating history of Stalin’s gamesmanship of the Central Committee in the early ‘20s. Of course, I don’t know if I can use that term in the same way any more – after all, we are now in the early ‘20s once more. And the whole way down, the glacier glowed an intense blue in the evening sun, tempting me to toboggan down it.

Alaska was a Russian colony before it was purchased by Seward, and I visited some of the beautiful Russian Orthodox churches that dot the Kenai Peninsula. In the village of Nikolaevsk, settling in the 1960s by Old-Rite Russian Orthodox, I even found an onion dome sitting on the grass, like you’d find a car in other rural parts of the country. Perhaps it was being patched up to be reinstalled somewhere.

On a different weekend, I traveled north to Denali National Park. Staying in a cabin next to a pack of sled huskies, I got a taste of the extended lilac hour, which in the Alaskan summer last much longer. The next day, I rode a bus into the park. Though I never got a clear view of the mountain due to its perpetual cloud-cover, I did see two bears, some wild sheep, and a landscape that looks like my romantic imagination of the Mongolian steppe.

One thing I loved about the summer was the proliferation of bright flowers. Here you can see a few of the ones I encountered, along with your typical ferny underbrush. The explosion of poppies is my nextdoor neighbor’s wild garden, and the low pink groundcover was spotted at the top of the Exit Glacier, where the dark stones were so warm from soaking up the sun that I laid down on them for a while. There’s a picture of Anchorage from above, and one of my favorite type of wildlife – the bumblebee.

I made one final trip that summer, and finally completed by journey to McCarthy. Along the way I crossed the Copper River, traveled through the some of the most glorious country I have seen, and finally came to a tiny town at the end of the last road. A couple miles uphill was the creaking ruin of the Kennecott Mine, which for thirty years was a bustling town with families and children and trains to the coast – and then just as soon as it appeared, it was all gone. But the ruin is incredible, and it sits just above a vast glacier, which appears like so many hills of dirt on the march. Just north of the mine, past fields of glowing fuzz, I was able to step onto the icy toe of the Root Glacier. My typically poor planning (or improvisational style, if you prefer) had left me unshod to go any further – but there’s always next time.

Krakow

When I left Auschwitz, I had to double-back to Katowice, going the wrong direction – that was the only way the train would go. It seemed the place did not wish to let me go; the ticket machine was broken. I was nervous about trying to buy a ticket on the train, speaking no Polish and being generally shy and very self-conscious about always following every rule, at least when abroad. Fortunately, I had met a young Bulgarian on the tour of the camps, who was in the same boat as me, only more at home on eastern European trains, and together we made it back to Katowice. He seemed a very nice fellow, and he explained to me that he controlled the stoplights in some midwestern city (I think maybe Oklahoma City, or perhaps Omaha) from his office in Sofia – a funny reminder of how tightly interlaced our planet is today. I wish him well.

From Katowice it was only a short ride to the east to Poland’s ancient capital, Krakow. When I arrived the city was grey, under November clouds, but as the light went out it became a place of high contrast – pitch black side streets opening onto brilliantly lit thoroughfares crowded with streetcars and buses, and lots of people walking here and there, eating street food in the subway underpasses.

In the morning, I rose and went out, and it was a bright and sunny day. I was staying on the southeast side of the city, in Kazimierz, what had been the old Jewish quarter of the town. The first sight I saw going down the street was the Remah cemetery, quiet and overgrown with green, even in autumn.

From there, I walked up a path that climbed the Wawel hill, the ancient castle of the kings of Poland, wrapping around it like a spiral. From the bastions, the view of the Vistula, one of the great rivers of Europe, was incredibly peaceful, and the brick towers were clomb with ivy, like some New England university.

Inside the castle was a hodgepodge of buildings of different ages, all run together around a grassy courtyard where the garden was planted among archaeological ruins. The crowning jewel was the cathedral, and over the gate hang the famous bones of the Wawel Dragon, which have decorated the cathedral for centuries. Dragon or not, the bones themselves are quite real, and are probably the fossils of either a whale or a mammoth.

Unfortunately I could not photograph the interior of the cathedral, a gorgeously baroque space of green marble and gilt decorations. I did climb the belfry, up ladderlike stairs squished between the gargantuan wooden trellis of the bells – and I’m glad those bells were silenced with wood beams, because they would have deafened me. Each bell was bigger than my car.

Then I passed down into the city, past the statue of Poland’s favorite son, John Paul II, and up the many cobbled streets, past ancient churches and vendors selling tourist knick-knacks, to the great market square and its famous cloth-hall, the Sukiennice.

There in the grand square, perhaps the greatest I had seen in Europe, a group of Ukrainians held vigil by a fountain, extolling their country’s plight, and, I presume, asking for aid (unfortunately I do not speak Polish or Ukrainian). These countries, once frequent rivals, are now knit together in solidarity. From time to time, as I wandered the square, I would hear them play music, echoing off the colorful facades, lamenting.

Then I walked to the north end of the city, to one of its many narrow gates. The wall is beautifully intact, the towers still high and proud, and the barbican stands before the gate in the joggers’ park that was once the city moat, no longer warding but welcoming.

Slowly, I made my way south again, past a group of vans behind the train station which seemed to be intended to help Ukrainian refugees in some way, perhaps with document processing – I could not be certain. I crossed the Vistula on a bridge flecked with frozen dancers, and there, on the south side, I stopped at two pilgrimage sites. First, the Apteka pod Orlem, a pharmacy whose owner and staff did all they could to aid the persecuted Jews in the ghetto there during the occupation. Then I went to the famous factory owned by Oskar Schindler, which served as an ark for many lives.

At night, the great market square, the Rynek Glowny, became a place of unsurpassed beauty, as the streetlights flared off the cobblestones.

Movies I Saw in 2022

Ok, I’m laughing at myself as I start this one. I’m not sure how many times I can make the joke about me posting something late, but in this case I almost have to. I meant to write this blog at the end of 2022; it is almost Halloween of 2023. Oh well lol.

I want to be very clear, this is not a list of films released in 2022 – I’m going to get to that in another post. I’ve also mostly excluded films released in 2021, because then it would be too heavily dominated by recency bias, especially since 2021 was a banner year for movies. The only thing these movies have in common is that I happened to watch them, some for the first time, some not, during 2022. I’m only going to run through a few titles here that I wanted to mention for one reason or another. In total, I watched 216 movies in 2022.

My Neighbor Totoro

I started the year off right; on January 1, I watched Hayao Miyazaki’s beloved classic, My Neighbor Totoro (1988). This is part of a subgenre of movies that depict rural Japan and which therefore crystallize a very specific sort of nostalgia for the brief time I spent toodling around the chequerboard fields of Funakura. Totoro is a sort of bright mirror, however, because my nostalgia is melancholic, recognizing my own peculiar adult faults and remembering a time where I was both very relaxed and happy, but also often lonely and sad. The film, on the other hand, depicts childhood joy in a way that seems innocent and free. Even so, it’s a film about children facing, in some small way, the anxiety of loss, which is why it has far greater staying power than a lot of other films aimed at children. It’s hard to see a way back to this sort of childhood joy, but I think it’s necessary to believe it’s possible – perhaps to return, to come, as Christ said, as a little child.

Other notes:

· Joe Hisaishi’s scores are always iconic, but this one is particularly magnificent, as anyone remotely familiar with it knows.

· The world is strange and twisted in a sort of unsettling-comforting unity. Cf. Catbus.

· This is the cinematic equivalent of “All shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

Germany, Year Zero

Only a week into the new year, I watched Roberto Rossellini’s stark film, Germany, Year Zero. Released in 1948, only three years after the fall of Berlin, the film takes place in the broken rubble of the desiccated city, and follows a child as he attempts, somehow, to live in a world of shards and ash. Personally, this film challenged the limits of how I think about the world, not because anything in it was surprising (I’ve read plenty about the period), but because I had to confront the fact that there didn’t seem to be a way to act correctly in such a situation. I tend to obsess over what people should do in any situation, how things should be – and Berlin after the fall laughs and spits in the face of such thoughts.

· This is a case of melodrama being fully justified by the actual state of things.

· This is a real case of that standard of fiction, the work that tries to picture what would happen to survivors of the apocalypse. We just usually like to look away from times when that actually happened.

· Part of the tragedy is the image of children with no hope, made even more poignant because, in the light of history, we know that there would eventually be cause for hope, and other things to live for. But I know how hard it is to see that in your own life, even in cases where you intellectually know it to be true.

The Worst Person in the World

I said I wouldn’t write about any films released in 2022 or 2021, but made that rule intending to break it for two movies, just to make a point about their greatness. The first is Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World. This is a strikingly beautiful movie (Oslo is filmed suffused in faded natural magentas and lavenders), and Renate Reinsve gives an astonishing, gentle performance. But more than anything, the film directly addresses my anxiety about wasting my life, and being a small, selfish person. And it reaches a profound and inexplicable state of catharsis, without fantastically compromising the reality of life depicted. If you read a synopsis of the plot, it wouldn’t sound like anything special, but that’s simply a testament to the importance of execution and direction. As it stands, this is one of my favorite movies.

To be completely honest, I don’t know how to relate to catharsis in art. I think that we desperately need it, or at least I do, personally – but my fear is that I arrive at a purely emotional sense of relief, and believe that all will be well, without that necessarily involving spiritual reconciliation. That seems sort of cold to say, and I’m not happy with that doubt; but I think this struggle of whether or not to doubt the cathartic impulse of the moment is, for me, of a piece with the struggle over limited or universal reconciliation and redemption, and that’s not something I’ve really resolved within myself. So when I encounter art that strikes the chord in my soul that echoes Little Gidding’s refrain that “all shall be well, and/all manner of thing shall be well,” I worry that I’m rushing to just accept a Gospel with no demands. But it is, on the other hand, a free gift. And Tolkien wrote about the sudden unlooked for turning, the surprising moment of positive resolution, and I think this feeling is in that tradition.

If that seems like a rambling and personal tangent, perhaps it is – but it’s the thing that most nearly intersects with my own life, and in that way it’s the thing that I have got to say. There’s a mirrorlike quality to the film, at least for me. In the scene were our heroine tears up, looking into the dawn, I felt the shock of reminiscence – I too have climbed the rocky hill in order to be able to weep joyfully into the dawn.

Phantom Thread

Another softspoken movie I saw, perhaps one of the most softspoken, was Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2017 film Phantom Thread, which I will not attempt to define in terms of genre or plot. It’s both very simple and extremely strange, and I think it’s a career high performance from Daniel Day-Lewis, which is matched by Vicky Krieps – a true battle of megawatt performances, conducted almost in whispers. This is the best PTA movie I’ve seen, a film with rich visual textures, a specific quality of light, the calm essential vitality of being. Everything is exactly right.

A Story of Floating Weeds/Floating Weeds

I’m cheating a little with the next, because I watched Yasujiro Ozu’s A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) in February of 2022, and then watched his 1959 remake of his own movie, Floating Weeds, in February of this year. The two have the same plot, and they are both superb. Ozu seems to have cracked the code, realizing that the best way to prevent someone from making a mediocre remake of your movie is to just make a great one yourself first. While the remake is more dynamic in some respects, and has the benefit of glorious Agfa red, a color God decorates heaven with, I actually felt more emotionally moved by the earlier film, especially by Emiko Yagumo’s tremendous mouth acting.

The Passion of Joan of Arc

Another extremely emotional black and white film I saw in February was the 1928 silent masterpiece of Carl Theodor Dreyer, The Passion of Joan of Arc. The film depicts Joan during her trial and, if you’re so inclined, martyrdom, and features the most and probably the best eye acting I have ever seen, from Maria Falconetti. The film is a fragile yet unvanquished image of defiance in the face of sneering, mocking evil, yet without the sort of romanticized erasure of human frailty and fear. I’ve always been scared by stories of martyrs, because I just don’t think I could endure such a trial. And yet, in this film, Joan remains human while becoming a saint.

Lady Snowblood

On a completely different note, Toshiya Fujita’s 1973 revenge classic, Lady Snowblood, is a luridly vivid splash of crimson blood that just rocks. But there’s a tremendous amount of artistry present in the design and direction – there are incredible shots of stunningly white snowy foregrounds within an inky void of black negative space – and into that, the reddest blood imaginable.

Millennium Actress

Satoshi Kon is one of the most beloved directors of animation, who passed sadly long before his time, after directing only four features. In March of last year, I watched all four in a row, and of those four, Millennium Actress is my favorite. The film is a nostalgic collage, blending memories from the life of the eponymous actress with fictive temporalities plucked from her movies. It’s a meditation on the way in which we construct our own nostalgic pasts, whether for gratitude or regret (to the extent that, in nostalgia, they even differ), and paste our memories and created stories together like newspaper cuttings. The imagined relationship that could-have-been becomes a sort of parasocial love affair with one’s own remembrances. The film creates the feeling of age, the sense of astonishment that a life can span so much time, so many different worlds; but it doesn’t only look backwards. Somehow, despite its fascination with nostalgic longing, with might-have-beens, the movie is robustly hopeful in ultimate outlook, and is all the more successful at cheering me up because it feels honest in its treatment of life.

Drive My Car

I said I would break my rule against 2021 releases for two movies, and the second is one which I have watched at least three times since its release, and which has now got the better end of the tie with Worst Person in the World for my favorite film of 2021: Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s monumental Drive My Car. There’s a lot of things to say about this movie. First, the titular car is one of the best-looking vehicles I’ve ever seen in film: a red Saab 900 Turbo. They don’t drive it fast (it’s Japan), but they drive it oh so well.

Second, this has the same thing going for it as Worst Person in the World, to the extent that I view them as somehow twinned. This is a movie about catharsis, about accepting that despite life not being what you hoped for or expected, and despite the wounds we wear, you will be ok. In some respects, this film is even more directly about that than the other, and so of course I can’t even really fully feel that sense of catharsis, without simultaneously feeling doubt – because the way I apprehend catharsis feels like a cheat, like smuggling in the attitude of implicit universalism, or a release from moral risk and responsibility. But I hope that one day, I shall be whole, not perfect, but able, at least, to feel that catharsis and peace when watching a movie like this, and not second-guessing.

Finally, the film has an incredibly cast, all of whom give fascinating performances. I think a lot of people have noted Reika Kirishima as a showstealer, and she is a strange, cryptic presence. The two leads, Hidetoshi Nishijima and Toko Miura, give performances that are all the more emotionally potent for their restraint, for what they do not say. I went into this knowing Miura as a musical artist, and I was surprised and fascinated by her character and presence. But the person who actually stole the show for me was Park Yu-rim. She delivers the culminating monologue of the film, a speech from Chekhov’s play Uncle Vanya, in Korean Sign Language, and in that scene, in near complete silence, the film fully articulates its message – that, acknowledging our pain, we still must live our lives in quiet hope. It’s maybe the best performance and definitely the best scene of the year, and I can’t stop repeating it, because I desperately need the seed of hope amidst reality that it contains.

Last and First Men

I also watched one of the best movies I’ve fallen asleep during (in fairness, I was very tired): Last and First Men. I first became interested in this because I stumbled across the music, composed by its director, composer Johann Johannsson. Sadly, this film was the culmination of his career, as he passed at a young age, so this is also his last and first film. I was so intrigued by the trailer that I read the book as well, a narrative of an imagined distant future, spanning eons of time, written a century ago by Olaf Stapleton. The film boils this story down to a spare monologue of narration by Tilda Swinton (of course). This plays over a series of still black and white shots of decaying concrete Communist monuments. And there are frequent pauses of a minute or more, in which the camera does not shift and the narrator does not speak.

In short, it’s improbable and surprising that this movie works – but somehow, it does. The central arc of Stapleton’s book is a civilization trying to cast about for any source of hope or meaning in a cold, bleak universe, where entropy will eventually run the clock out on history. Johannsson managed to find the perfect way to represent the epitaph of hopeless time in the monuments of a failed regime that gestured toward a better future. It’s haunting and beautiful, even if it does put you to sleep. Having said that, I’m glad I don’t believe in a universe in which the cold heat death of material processes is the final word on life.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

Peter Weir directed the second-best movie of the 1970s, an esoteric, meditative play of soft light and sleepy, otherworldly vibes. But that’s not what I’m here to talk about, because in 2003 he also directed what must be the greatest tall ship movie of all time, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. I have extremely complicated emotions about the British Empire (a villainous enterprise of exploitation that created the world in which a disproportionate of the culture I grew up with and have nostalgia for was created), and by extension, the Royal Navy, but my emotions about this movie are extremely simple: it’s great! Part of it is that I love movies that show professionals at work, executing processes with aplomb; part of it is probably that the RN is the prototype of my beloved Starfleet, the example par excellence of that sort of professionalism (it helps that Crowe has a Shatneresque energy to him). I think ultimately, there’s nothing as romantic as a tall ship on a wide open sea.

Boyfriends and Girlfriends/Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle

In short succession I watched two of Eric Rohmer’s little films (I use the term affectionately, not pejoratively), Boyfriends and Girlfriends, and Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle. I feel like these quiet pieces, in which little seems to happen except for ordinary life, with warm colors and a gentle spirit, are mining the same vein as Ozu’s later work. I also have a very strange nostalgic fascination with western Europe in the 1980s, possibly based on architectural books I read as a child, and these films fit nicely into that grain.

The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun

In May I watched The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun, a film by the great Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty, and this short movie feels like some sort of perfectly cut topaz or amber gem. The whole is encapsulated in the part, in one sequence when the characters go dancing down the street in a way I can’t really even describe – but it’s electrifying.

Atonement

I also watched Joe Wright’s 2007 film, Atonement, which I had been meaning to get around to for a long time. For me, it’s a fascinating collision of nostalgia and antinostalgia; longing for worlds which never got to exist, and, at the same time, rebuking that with harsh reality, nostalgia collapsing into guilty regret, and all played out against the backdrop of a wartime England that is, for many like me, a site of great nostalgia, but which was also at the epicentre of the ultimate collapse into imperial guilt and regret. It’s also a gorgeous film, which includes one of the most successfully elegiac sequences I’ve ever seen.

Dodes’ka-den

Everyone loves Akira Kurosawa, and I’m no exception. Working my way through his filmography, I came upon Dodes’ka-den, and was shocked that the great director had made something simultaneously so artistically compelling and successful, and so – well – ugly. I thought I knew what sort of films Kurosawa made, and was very comfortable with them, but this was jarring and nauseating. It’s never going to be one of my favorite of his films, given my sentimentalist, cathartic biases, but I’m going to remember it with great respect for the truth it depicts.

The Virgin Suicides

The Virgin Suicides is as good an argument for nepotism as you can make. Personally, I think it’s probably Sofia Coppola’s best work. It manages to crystallize an incredibly specific sort of narrow hopelessness one gets in adolescence, when you can’t actually see a path into the future. To the extent that this is the condition of mortal life, it’s a universal text, even though all is portrayed through an extremely particular suburban moment.

Juno

When I watched Juno, I had no expectation that I would be so thoroughly won over by it, but the film is so winsome and charming that I had to watch it a second time in short succession. It’s the perfect combination of wit and sincerity. And for all that this is a dialogue-driven film, the most powerful line in the movie is read, not spoken. What an optimistic little movie!

Silence

I think the greatest and most profound movie I saw in 2022 was Silence, a movie that so transfixed me that I not only immediately read the novel it was adapted from, but also read someone’s dissertation on the hidden Christians of the southwestern islands of Japan. In my view, this is Scorsese’s best film, but that’s not the most surprising thing I could say – this movie was designed for me in a lab. It combines calling out to God, trying to hear Him respond, with deep practical theological angst, and all of that through a beautifully reconstructed early Edo-period rural Japan. I don’t have the same sort of complex the protagonist does, but I remember in childhood being anxious about the idea of tests of faith in martyrdom. I’m not even sure what I think about what the film seems to be suggesting about pride and martyrdom, or mercy – I think I may actually not agree, if I’m understanding it correctly – my view of the potential value of martyrdom is perhaps not deconstructed much at all. But I love the incredible sense of empathy the film has, and as a weak person, it seems to be begging for room for those of us who are weaker. And, without spoiling anything, I will say that I have often been sitting and thinking, and the final shot of the film will come unbidden to mind, and I will begin to cry.

Andrew Garfield should have won Best Actor for this, and someone in the staggeringly good cast of supporting actors should have also walked with an award – take your pick as to who.

Paris, Texas

Paris, Texas honestly wasn’t doing that much for me for most of its runtime. I could tell it was well-crafted and looked nice, but it just wasn’t connecting – until the end. The last conversation through glass really broke through to me, and I was left reflecting on a story about what love is after you feel you’ve lost your right to it, yet still find it extended nevertheless. It’s a picture about grace.

Days of Being Wild

Days of Being Wild, another Wong Kar-Wai movie in which the director wonders what would happen if everything was teal, is a film where you can actually feel and smell the humidity as you watch it. And it captures the dread anxiety of knowing that you’ll hate yourself if you do something that you’re nonetheless drawn to, even as you feel anxious that you don’t want to hate yourself. Possibly his best film I’ve seen? I really will have to think about it.

Whisper of the Heart

Whisper of the Heart was made by Yoshifumi Kondo, the man trained to be the successor to Miyazaki and Takahata at the head of Studio Ghibli, but he tragically died after only directing this one feature. Miyazaki has made 12 movies; Takahata made about 7, I think. Yoshifumi Kondo only ever got to make one. His movie is as good as the best movie from each of the others; it’s on par with the best thing any anime director has done.

You might not believe this, but it's true: near the beginning of this film I paused because I was sad and discouraged, by two specific feelings, not because of this film but occasioned by its hopeful sentiment. First, that my life would never make sense like a story does, and second, that it has declined, and I no longer enjoy things as I did, or am as good as I was. Then, almost halfway through the movie, our heroine voiced exactly those same feelings. Now, maybe I have more cause to be anxious about life not making sense, since I'm much older, but still, it's something. This is a deeply hopeful precious gem.

A Hidden Life

I watched Malick’s A Hidden Life alone in a room in the Catholic center for dialogue and prayer a block away from Auschwitz. It seemed the right place for it. Once again I feel that Malick has perhaps the best grasp on the Beautiful and Good of anyone working; he also has the strangest way of editing conversations I’ve ever seen.

Talking about our comfortable idea of Christ, as opposed to the Man of Sorrows, and thinking about how we live, and try to avoid suffering, is really challenging for me, and speaks into a lot of my anxiety about what I should or shouldn't do, but don't. I struggle with heroic narratives because they suggest a higher moral possibility than I want to have to contend with. I just have a lot of anxiety about the consequence of the divide between people who will die for the truth, and those making excuses not to, since I feel like someone who makes excuses to do the easy thing.

Moulin Rouge!

I realize that Moulin Rouge! elevates adolescent feelings and crushes to the level of something noble and true in a way that doesn’t fully pass scrutiny, but it’s just done so compellingly and with such unembarrassed sincerity that it always wins me over. It’s both a sentimental picture of romantic, emotional love defeating cynicism, and a deeply comic film in which a coquettish Jim Broadbent grunts out Madonna lyrics (he should have gotten an Oscar for this).

First Reformed

On First Reformed, a film I took very seriously but was deeply puzzled by: I have never quite known how to process really serious arguments about the warnings on climate change, because it's such a challenge to my own desire for optimism and my rootedness in the idea of the status quo, the idea that some things get worse and some things get better, and it all evens out and we muddle through like we always have. I know that there is a religious and eschatological answer to all of this, which I believe in, but it's difficult to foreground that because of my own anxieties about eternity, and because of my reaction against the end times obsession among Evangelicals when I was growing up. Maybe all of this is just the recognition that while I believe the climate models and think more needs to be done, I’m less willing to significantly change my lifestyle, and unwilling to ask others to forgo ascension into the middle class, so maybe I'm just unwilling to do triage, so firmly do I have to believe in a possible future that is better than the present, and not worse - and now we're back to eschatology and eternity, and the fact that we're all deluding ourselves the moment we forget Death. But we also must live here, now, and our children. And I will say this: I’m not really an activist, and I don't tend to support radical sacrifices. I don't support denying the developing world power, and I don't support seriously reducing the middle class lifestyle, although I worry about how that interacts with my Christianity, given Christ's call to deny ourselves - but I don't want to fall into a kind of Puritan impulse to sacrifice for its own sake, that life has to be hard. And I will also say that I think it is good to bring children into the world, even this world. But this all just sets off my anxiety of conviction - in church they say we have to change, and I feel unwilling, and am anxious, and in the political sphere activists say we need to change, and I feel unwilling, and become anxious. It's tiring, although maybe that's an excuse. I think I've just never really been able to get around my sense of anxiety about certain kinds of disruption, perhaps because there's no clear limit to it, or perhaps just because I don't want life disrupted with no sense of control over it. And I think I've never fully been able to get on board, because while I can be appalled by the destruction of the forests, I always am thinking about civilization and its maintenance, and there's a part of me that worries it doesn't work if too much is changed. It's like when people started singing about removing dams - immediately I thought, "dams are important, though - you can't realistically impound enough irrigation water for droughts without them." But I worry that makes me a bad person. I think that cui bono is the right question, and I think the distinction between me and some folks a little further to my left on this is that some of them would focus that answer on large corporations and the holders of global capital, while I am always worried that actually, it's not just them, it's all of us, too. And I have no idea what to make of the ending.

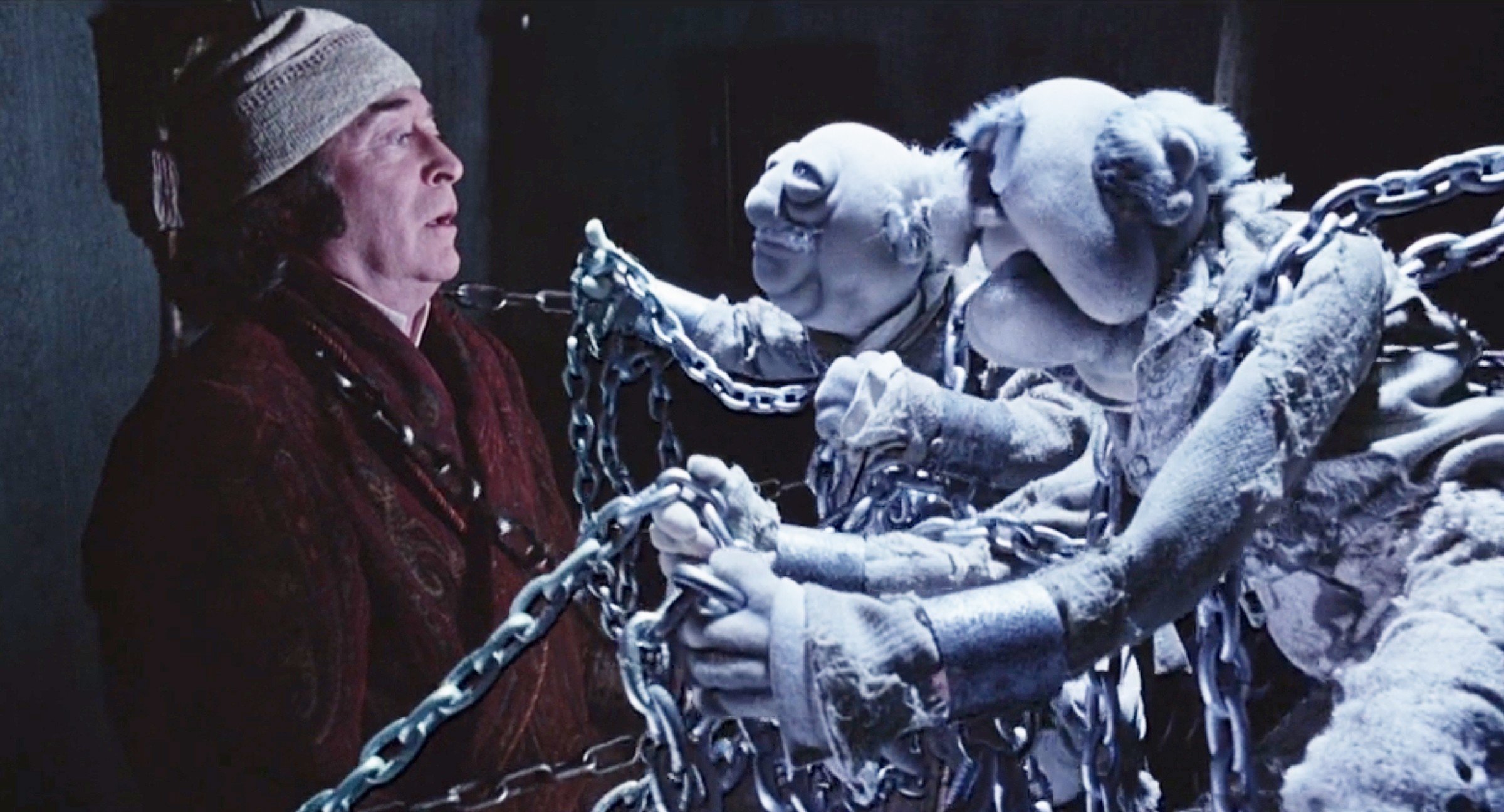

The Muppet Christmas Carol

I ended the year with the greatest Christmas movie of all time, The Muppet Christmas Carol, finally restored to the original version I remembered from my childhood VHS, with the crucial song that was bizarrely cut from the DVD for many years. This movie is somehow one of my favorite films of all time, even though it provokes my fear of hell and the pressure of some sort of works-repentance soteriology. Maybe that sounds like a silly reaction to Statler and Waldorf in ghostly chains, but it’s a real thing I struggle with, so it’s interesting that my affection for this is unimpaired. At any rate, the deeper pattern of the story rings true, and Caine gives an incredible performance. There’s no reason you couldn’t make any story, with every bit of its seriousness and sentiment, with muppets.

Auschwitz

In all honesty, I didn’t want to write a blog about visiting Auschwitz. It’s a serious place, and I’m not a very serious writer. What happened there is well known to us all, and I have nothing to add. Given this, it feels almost in poor taste. However, I decided I would write about my trip and the places I went, largely as a way of contextualizing and sharing my photos, and I’m not going to skip over perhaps the most important point I reached.

It was a surprisingly long journey by train from Prague, partly because the train idled for a long time near the border, partly because the town of Oświęcim (it’s proper Polish name) isn’t really on the way to anywhere. It’s out in the flat green countryside of southern Poland, and to get there I had to connect through Katowice and then go by local commuter rail. By the time I arrived it was already quite dark and cold; from the brightly-lit & recently rebuilt station, I walked about a mile along dim roads to the other side of town. There was nothing particularly historic or interesting along this way; just blank asphalt and miscellaneous businesses, a cheap restaurant here, a tire shop there. I’m not being quite fair to the town; I don’t think I really went to the best parts of it. That’s not why anyone goes there.

I stayed at the Catholic Centre for Dialogue and Prayer, built only a block from the first camp. It was as silent as the town around it, simple and spare. That night I watched Malick’s film A Hidden Life, about a conscientious objector from Austria during the war. It wasn’t directly related to the place I found myself, but it seemed apropos, felt correct.

In the morning, I toured the camps. For me, what surprised me most, although on reflection it shouldn’t have, was how normal everything felt. You arrive at what might be the single most horrifying place on earth, which is also an immense grave, and you come having been prepared for it by a lifetime of history and media. You expect great sorrow, and a sense of weighty reverence; you expect, perhaps, to cry. But mostly it just felt a little muted, a little hushed. It’s not a normal place, and yet in some sense it is. It was a sunny day, and everything felt very calm, and if you don’t have a direct connection to the place, it actually seems right to just be interested. It’s not really about you, after all.

Auschwitz I is in the town, and consists of normal brick buildings, with rows of trees and broad avenues. When you’ve been in Europe for two weeks, spending as much time as possible in the historical centers of cities, you almost don’t notice these buildings because they are so unremarkable, so dull. But that is itself the striking thing: these buildings are so modern, so much more recent than the average place you might stay in Europe, that they aren’t even worth noticing. That in itself is the greatest reminder of just how recent, how modern and contemporary this place is.

The interiors of the buildings create a double-effect, both emphasizing this sense of false normalcy – the flooring reminds me of the cheap tile still found in schools when I was growing up – but the rooms are filled with the detritus of lost lives. There are barracks, spare and uncomfortable, and yet not as bad as they would become at the second camp; there is a room, maybe fifty feet long, containing a pile of shoes that long and higher than my head; there is a whole room of crutches and prosthetic limbs, a reminder of the deliberate destruction of the disabled; there is a room of used canisters of gas; and there is an urn of human ashes, of who knows how many.

There was also a room which one is not allowed to photograph. This room has a pile as big as the pile of shoes – I would estimate perhaps fifteen feet deep, six feet high, and fifty feet long, though I have never been good at distances. This pile is made of women’s hair. It still retains some of its color – mostly brunette or grey, here and there a lock of blonde.

Outside is a yard where prisoners were shot; there’s a long gallows, where a group was killed after an uprising. And there is the first gas chamber and crematorium, still intact. The larger ones at the second camp were destroyed at the end of the war, which in some ways feels like a blessing.

Next to the gas chamber, only a short distance from the villa he lived in, stand the gallows on which the camp commandant, Rudolph Hoss, was executed after the war.

From Auschwitz I, it’s a short trip across town to the much larger Auschwitz II, the camp designed expressly as a death camp. This place feels surreal, simply because the image of the gate, with its guard tower, and the rail siding where people’s fate was instantly decided, are so etched into the collective cultural memory. It’s one thing to visit an old ruin, but it’s quite another to visit a place you’ve seen in film and historical photographs, and have it look, at least in parts, exactly as you are used to seeing it, only in color and sunlight.

There’s little more to say. Most of the barracks were destroyed, but a few still exist; there’s an example of one of the infamous rail cars. The gas chambers and crematoria are in ruins. Behind them is a large monument, with warnings to the future, reminders about the crimes committed, written in a dozen languages. Next to one of the gas chambers is a sort of sunken pond, a pit of grey mud, made of human ashes. The entire site, and the peaceful birch woods behind it, and the surrounding countryside, are all a grave – there is ash under the grass you walk on, under each rock and tree, extending out from there into the world, who knows how far.

February 2023 in Music

All right, back again. Music that I enjoyed listening to way back in February.

Song for Dennis Brown and To the Headless Horseman, The Mountain Goats – I think that John Darnielle is the best lyricist in America, and I have listened to a great many of his songs. Maybe they appeal to me because they tend to be melancholy and seem to important aspects of life, but in extreme particularities and funny little details; maybe it’s because he’s so poetically fluent in religious language; maybe it just seems profound because of the gentle roughness of his delivery. Whatever the reason, I think the world of his work, and these are just a couple of minor samples – they aren’t even anywhere near the top of my list. But they are typical of his work, because they feel like the poetry of someone anticipating his own death.

Drive My Car (Kafuku), Eiko Ishibashi – This is the titular track from Eiko Ishibashi’s score for the eponymous 2021 movie, Drive My Car, a film essentially locked in a tie for my favorite film of that year. When I watched it, I admit I didn’t think about the music that much; like the movie itself, it sits quietly in the background, and is the opposite of showy. But once you do notice it, you realize that it’s perfect, in its quiet introversion. This music feels like being driven somewhere, fast along the highway, into the night, and while it’s peaceful, it’s also struck through with strange chords that mar that peace with doubt.

Songbirds, Homecomings – Songbirds is an attempt to catch some scintilla of remembrance, to crystallize a moment into nostalgia before it can flutter away. It feels warm, like the sunlight late in the afternoon in winter, caught in the glass. Homecomings are terrific at exactly this sort of warmth, sad, yet deeply contented.

I know Songbirds because it was featured in the best film of 2018, the extraordinarily quiet and restrained anime film Liz and the Blue Bird. The next three tracks on my playlist are all from the score to the film, two by Kensuke Ushio, a master of hushed tones that fit the quiescence of the picture, and the titular piece, Liz and the Blue Bird, composed by Akito Matsuda, which is the piece the film’s characters perform in band and practice throughout the film. It’s a tentative, questing piece, driven by woodwinds, and it successfully tells the story of both the film and the picture book at the center of its plot. As for Ushio’s work, so much of it sounds like the diegetic sound of the school the characters inhabit – in fact, much of that is incorporated into the score, and then echoed instrumentally. In a story where everything is tiny details, this is a masterful success at using score as a seamless instrument of narrative. As music on its own terms, it is so enormous in its tiny, restrained softness, like feeling the heartbeat of a sparrow, that it both places me in a trancelike state, while also bringing me to tears.

Golborne Road, Nick Laird-Clowes – this is part of the soundtrack to the excellent film, About Time, and there’s something about the way this simple piano piece that feels like it acknowledges melancholy while continuing forward undeterred, into the wind. Maybe it’s the quick repetition of notes where some stray into both minor and major – it’s always teetering on ridgeline between mourning and joy.

Since You Been Gone, Rainbow – I think I had another song used in a Guardians of the Galaxy trailer on my January list, and this one has the same story for me. I’d never listened to or even heard of Rainbow, but it’s another case of ‘70s rock that is big and fun and you have to bob your head along to it. I’ve nothing insightful to say about it, it’s just a good time.

Blue, Mai Yamane – Blue plays over the end of the show Cowboy Bebop, which I’ve mentioned before, and like its mid-season counterpart Space Lion, I found it immediately arresting and moving. The more I returned to it, the harder it got to move on from it. The song is an elegy, mixing a children’s choir singing Christian praises with operatic rock that presents the final sense of release from bondage experienced by a soul ascending from this sublunary world after death. I admit I am particularly sensitive to depictions of transcendent apotheosis, but this is beautifully executed, and achieves both sentiment and that most prized (by me) of musical achievements – maestoso.

Kazehi, Zmi – This is a great case of the Spotify algorithm handing me a good example of the sort of thing I listen to – gentle, brief piano from Japan. I don’t have that much to say, but of course this brings me to the last couple of songs, from my favorite musical artist, the prototypical master of that same genre:

The Story of Sky & Team, Takagi Masakatsu & Sakamoto Miu – The first track feels like breathing, in and out – not the breath of anxious struggle, but what one imagines actual peaceful breathing to be. The piano dances like seafoam around the vocals which carry us on our own journey through a garden of clouds. And Team is one of many demonstrations of Takagi’s power to make an uplifting and wild piece that in its energetic and vivacious spirit still fully retains the deep sentimentality that pervades all of his work. Where that sentiment is located, I can’t precisely say, I only know that all of his music moves me in some profound yet ineffable way.

Prague

From sepulchral Terezin I took the train south to vivacious capital of the Czech Republic, one of the most celebrated European cities, Prague. The city spans a great bend in the Vltava river, a major tributary of the Elbe, and grew up around a high fortress overlooking a ford in the river. Now the city seems flooded with tourists and partiers from all over Europe. Its place on the river crossing befits its history; Prague has frequently straddled the line between west and east, forming at one time part of the eastern edge of the Holy Roman Empire, and at another sitting as the western edge of the Warsaw Pact. The Czech Republic is the westernmost Slavic nation, but most of its history has been spent under German rulers as the kingdom of Bohemia, surrounded by German lands on three sides. Unsurprisingly, there’s an eclectic and rich variety of architecture.

While Terezin was cool and grey, when I arrived in Prague the city was in its October glory. The waterfront along the Vltava was in an almost constant sort of sub-magic hour glow, the air visibly suffused with honeyed light. Holidayers paddled on the river or crowded restaurant patios as children played under the leaves now browning in the autumnal oven.

Walking north into the old town, the lanes narrowed and the architecture intensified its gothic fantasies; but at the street level, the facades gave way to an endless carousel of trinket shops, weed shops, and one place claiming to only probably have the best burgers and hotdogs in town. It was as if Times Square had been poured into a maze of medieval lanes, seeping through the closes like syrup.

For the first time I saw a beggar kneeling, perfectly still. I’m used to beggars and panhandlers, but to see someone kneeling in what must have been an incredibly uncomfortable position for who knows how long still shocked me.

Then I came suddenly to the greatest attraction at the center of Prague; the ancient King Charles (not the one you’re thinking of) Bridge, and found its cobbles packed to bursting with every other tourist who had beelined there just like me.

In the square adjoining the bridge, a church bore this legend, another reminder that I was drawing closer to the part of the world still under the Russian shadow.

After a brief pause, I plunged into the stream of people and swam across the bridge, a salmon forcing its way upstream. Besides the magnificent towers and glowing views up and down the river, the Charles Bridge is lined with a panoply of stone figures, an outdoor statuary free to anyone willing to brave the crowds.

From the bridge, the road climbs through ever statelier neighborhoods, past domed cathedrals, up a great flight of stairs, to the castle square high above the town.

The second day I was in Prague, I passed the headquarters of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia, which I believe is the only still-active Communist Party in a former Warsaw Pact nation. They don’t seem terribly threatening now; they haven’t managed to secure a single seat in parliament.

There’s a lovely big square in the center of right-bank old Prague, just past the Powder Tower (above), which features the place where the protestant rebels were executed after the battle of White Mountain; those sympathetic to the cause of either Protestantism or Czech independence from Habsburg dominance regard them as martyrs. Nearby, surveying the crosses which mark their deaths, is a looming statue of the proto-protestant reformer Jan Hus.

At the north end of the old city is the Jewish Quarter, which once had one of the largest and most flourishing Jewish communities in Europe. I spent a good part of the day wandering between synagogues and cemeteries, and learning about all the ideas and creative work that was done in the face of immense obstacles, by people whom popular history has often reduced to passive unfortunates.

That evening was Sunday night, and I crossed the river to the North shore. Wanting to be with others with something in common, I visited a small missionary church where English served as the common tongue for people from all over the continent and world. Refreshed, I walked back through the soft night of rustling leaves. There is a temperature that obtains in the evenings in temperate countries in the fall that has somehow the crisp freshness of cool air but also the spreading warmth of a humid summer night: it is exactly correct.

The park on the northern bank overlooks the city from a cascading wall of staircases and trees, and at the summit is a grand pediment, which now holds what is almost certainly the largest metronome in the world. It upheld the largest monument to Stalin, which was dynamited during de-Stalinization, and today the metronome bears the legend that “in time, all things pass.”

On the last day I spent in Prague, I visited the great castle. On my way up the hill, I encountered yet another reminder of the spirit of resistance still vital in what was once Communist Europe. From the balustrade of the castle square, you can see a reminder of that – the looming Soviet communications tower, now an incongruously picturesque artefact for nostalgia.

The gem in Prague’s crown is the Cathedral of St. Vitus’, which contains, among others, the tombs of St. John Nepomunk, a priest killed for upholding the seal of confession, who was then heavily promoted as part of the counter-Reformation, and the tomb of Duke Vaclav I, or as you may know him, Good King Weceslaus. He holds his place in the great European tradition of Saint-Kings who are revered as both the temporal founders and spiritual patrons of their nations, and which accrete all sorts of legends. He was supposedly murdered by his brother, Boleslaus the Cruel, and I’ll let you guess why we don’t sing any songs about him.

The castle also contained a much older church, a narrow lane filled with the homes (tiny!) of various craftspeople, particularly goldsmiths, the Crown of Bohemia (which was unfortunately not for sale, apparently), and, of course, the Window of the Defenestration, from which the Habsburg’s officials were thrown in the Third Defenestration of Prague (yes I know). They fell seventy feet, and were either saved by the Virgin Mary or by a dung heap, depending on whether you ask Catholics or Protestants. At any rate they survived, and the defenestration went down as both a nationalist and a religious rebellion, and one of the key inciting incidents of the terrible Thirty Year’s War.

Finally, I returned to the city, slept, and in the morning, I took the train to the East.

January 2023 in Music

Way back at the end of last year, I had planned to blog regularly about the music I listened to each month. To that end, I dutifully made one playlist at the end of each month, starting with January. However, I was immediately halted by two lions at the gate: first, as I’ve mentioned before, I don’t actually know how to write about music. Anything I say on the subject tends to either become a stilted aping how more sophisticated aficionados write, or a repetitive yet genuine expression of the theme “hey, I like this, I like this a lot, you should too,” and so on.

The second lion was even worse: it’s easier and more fun to make a playlist than it is to write about it. Consequently, it is now September 23, and I am posting my playlist of music I enjoyed in January. In the past I would have just packed up and deferred the project to another year, but I’ve come to realize that if I don’t do something late, I probably won’t do it at all. So here we are.

Caveat – as I mentioned, I’m out of my depth. I’m not a music writer; I just gesticulate and riff.

Clarification – this is just some music I happened to listen to a lot in January 2023; it’s not actually music from January 2023, just to be clear.

All right, here goes:

Goodbye Stranger, Supertramp, 1979 – I had never listened to Supertramp before, but I ended up playing this constantly after it showed up in the Beau is Afraid trailer. Now, there’s a little bit of a spoiler here, but the trailer, while obviously indicating that the film will be dark and even upsetting (I mean it is Ari Aster), seemed to me to suggest some sort of catharsis on the other side of that, and the song’s optimism became entangled with my own fascination with any gesture toward transcendent catharsis – toward a revelation which makes emotional sense of a bad situation. It turns out that’s not really what the film is about, which is why I didn’t like it that much, though I respect how well-made it is and how well it does what it was trying to do, even if it wasn’t what I expected. But this song retains its earworm quality, probably because of the rising falsetto – there’s just not a lot of that out there, and it’s incredibly sunny.

Pandora, James Horner, 2009 – I went back and revisited the late great James Horner’s score for the first Avatar film on the occasion of watching its sequel. I’ve come to appreciate the franchise more over time, and I don’t think I had really paid that much attention to the music when it first came out – but I should have. Horner creates a vast space within the score, and uses it almost as an additional form of sound design, to place the listener in a world that feels vivid and exotic and, above all, fresh with promise. This feels like someone crossed Adiemus with a jungle version of Horner’s forest-sound score work on The New World.

Ocean Lights & Peace of Mind, Takagi Masakatsu, 2021 – I have said before, and here reaffirm, that Takagi Masakatsu is Our Greatest Living Composer, and I will be here for anything he does. I’ve listened to so many hours of his music over the years, it’s hard to even estimate how many. But Takagi tends to post proper albums sporadically – about half, or actually probably a bit more than half of what he posts are albums of marginalia, collages of musical notes – though those are also quite good. Recently, however, he put out a series of scores for a Japanese TV show I’ve never heard of and know nothing about. To be honest, it looks incredibly low budget, but if Takagi is writing music, I’m going to listen to it, and he does not disappoint here. Ocean Lights feels like the swelling march of the waves, proud and happy, carrying me along with no resistance. Peace of Mind is another collaboration with the singer Ann Sally, who featured on his greatest work, the score for Wolf Children. Sally has an incredibly delicate approach to each line, and it really does live up to its title.

Tank!, Rain, & Space Lion, SEATBELTS & Steve Conte, 1998 – I finally sat down and watched Cowboy Bebop, the ultimate classic space noir from the 90s, a show that I think sits at the center of a straight line from Star Wars to Firefly and then every single other down and out ragtag band of space misfits in contemporary fiction. Bebop has an incredibly soundtrack; it’s jazzy and big and totally unembarrassed by pretentions to restraint, and the first two tracks are great examples of that. But Space Lion is more than that – I kept coming back to it, because it really captured one of the emotional high points of the series, and held it, like starlight in a glass. There are a lot of big, emotional scores out there, but very few of their highlight tracks start with a hazy saxophone solo. But the moment the drums come in, and then the choir, the temperature shifts; it’s like the sun going down, and the aurora slowly unfurling itself, revealing that it was always there – you just weren’t looking.

Welcome Home, We Know What You Whisper, & Wakanda Forever, Ludwig Göransson, 2022 – Ok, so this score did come out right before January. I don’t want to go into a huge tangent about the Black Panther sequel, because I have so many thoughts about it (I think it’s flawed but still the most interesting Marvel project in a long time, and I generally liked it, certainly more than a lot of the recent output). So, without getting bogged down in all that interesting rabbit trail, let me just say that Göransson is having a fantastic year (I expect his Oscar will be arriving in a few months for Oppenheimer). I feel that in all the discussion of this movie, the score almost got neglected. People were really impressed and excited about the original Black Panther score, and rightfully so, but this is actually more interesting to me, because of how well the score shifts to not simply repeat the themes of the original in a kind of nostalgia (which I’m sure audiences were ready for). Instead, it swerves, not only into a darker vein, but one which reflects the environmental shift in the film; Wakanda Forever is colder, bluer, and there’s a marked shift toward the science-fiction aspects of the world. Just like the attempts to revive the herb by a synthetic process, the score takes the earthier beats of the original, and grafts them into a substrate dominated by cold electronic noise. These tracks are standouts, and my favorite is the one that shares the name of its film – it sets up a new theme that is synthetic and electric blue, and I remember when it played in the theater it felt like being in a vibrating prism.

Free Bird, Lynyrd Skynyrd – All right, ok, this one got in here because it’s a meme. But you know what? It’s a good meme. Zoomers rediscovering the power of classic rock through silly tiktoks is what intergenerational perpetuation of American culture looks like in the twenty-first century. But actually if I’m being honest, I had never listened to Skynyrd before either, so I’m in the same boat with the youths on this one.

The whole point of this one is the transition point where it switches from a lazy, mellow riff to a propulsive guitar solo, a bifurcation that reminds me of Layla (one of the best rock songs of all time). The thing that finally got me nodding along with this meme like a grinning Jack Nicholson was a video where someone posted nine minutes of a rocket sitting on the launchpad and then finally launching, with ignition timed to the song’s transition. To me, that is cinema.

I already talked about Friday I’m In Love (The Cure), and the main title from Andor (Nicholas Britell), and the music from The Rings of Power (Bear McCreary) in my post about music I listened to in 2022. That they still are on this playlist is endorsement enough. But I really want to emphasize the particular nostalgic sonic space created by The Cure in this song. There’s something about that moment at the end of the previous century that tinged music with an upbeat melancholy that’s hard to explain and impossible to fake.

Once in a Lifetime & Take Me to the River, Talking Heads – I finally watched Jonathan Demme’s legendary concert film Stop Making Sense, and I am very late to the party but I am happy to be here all the same. The sense of disorientation at the passage of time, the moment vanishing rapidly downstream even in the midst of endless repetition through time is only going to get more resonant as I get older, isn’t it? Oh dear.

Storm Is Coming, Junkie XL – The most iconic track from the mechanical tornado that is the Fury Road score needs no introduction to anyone familiar with the movie. It’s so easy for this sort of choppy, dramatic, overcranked score to slip into generic noise, but this transcends its genre to loom like the threatening sandstorm of the film, monolithic yet dynamic. Midway through the track, the wind’s dark melody overpowers the throbbing engines, and reminds humanity of our place.

The Visitors/Bye/End Titles from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, John Williams – I think this monster of a track can hold its own with any other example of Williams’ work. It mirrors the film in movement from darkened confusion, rising into clarity of vision, the apotheosis (which is exactly what the UFOs function as). This is as good an example as any of the classic Hollywood string sounds of outer space – climbing and spiraling ever higher. Finally it breaks into a majestic euphony of bells and horns and strings, rising upward through the clouds to touch the stars above, where it resolves into a tremulous choir. In the end, it feels more open than closed, not definitive, but posing a final, unanswered question: are we alone, or, not?

Balcony Scene from Romeo + Juliet, Craig Armstrong – This manages to mirror the tentative, questing, fearful-yet-hopeful feeling of the young lovers undone by a heaven glimpsed through the silly honesty of a teenage crush. I latched onto this song specifically because there’s a line that repeats over the end of the track, glancing up and down, which breaks like lightning over the melody, and smells like wet grass in spring.

In The Meantime, Spacehog – Like the first song on this playlist, I discovered this through its use in a movie trailer, in this case for the third Guardians of the Galaxy. It’s just a rollicking great rock song, impossible not to be carried along with, up through the atmosphere into the far out wilds above.

This Is to Mother You, Sinead O’Connor – When I made this list, the great Irish artist was still with us; I didn’t yet know that this was her last year, and in fact, I had just recently starting listening to her music. There are so many fantastic songs she left us with; this one has a certain redemptive, healing sense about it. It’s a gentle work of comforting grace – and don’t we all need just that?

Wild Horses, The Sundays – The Sundays, who only put out three albums over the first seven years of my life, have in retrospect become one of my most beloved bands. All their work has an echoing wistfulness, and this is a great example of that. It’s about the strength of affective attachment, paradoxically expressed through the unconstrainable nomadic strength of the horses.

Aettartre/End Credits from The Northman, Robin Carolan, Sebatian Gainsborough – This entire score is excellent, but the final track captures the wild breaking in of what is now an ancient, alien vision of the world and what lies beyond it, plucked strings drawing together, towards some fated collision with eternity.

Breakfast in America, Supertramp – We end with the same album with which we began. To be honest, this is an enormously goofy song, and it gets sillier the more I listen to it; but I enjoy that. A stereotyped, foreign caricature of America as a land of wealth, expressed with silly tubas yet in a minor march – there’s a lot here to enjoy, and who said music has to be serious to be good?

Terezin